I HAD planned to drive to my hometown, Panama City, for my father’s birthday on October 11. A few days before the intended trip, I was on the phone with my mom, and we discussed the tropical depression that had formed in the Caribbean, that would probably move north through the Gulf of Mexico and impact the Florida Panhandle.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I’ve driven through worse. I’ll pull over if it gets too bad.”

In just a day, plans changed. Hurricane Michael was coming, and strengthening as it did. I would not be driving home. I would instead be watching online updates and texting incessantly with friends and family.

Dad was going to stay in the house, the one that I grew up in, the one on a small bayou on St. Andrews Bay. In his defense, it was a Category 3 when he made this decision.

My mom and my sister’s family retreated inland, to the complex of medical offices where my father worked, where his group of orthopedic surgeons have their own X-ray facility with lead-lined walls, which could be retreated into if things got really bad.

We had previously followed this strategy when I was a child, though then my father had accompanied us.

The eye made landfall in the early afternoon of October 10. I lost contact with my family shortly after that. We all use Verizon, and their service would be knocked out for over a week.

I spent several tense hours not knowing what was going on, watching the intensity of the damn-near category 5 hurricane on the news. Nobody had predicted that it would land with so much strength.

Finally, in the evening, I got a call from my sister, Audrey, from a friend’s AT&T cell phone, but it was still choppy and garbled. The medical complex had survived, but she thought that if the storm had moved through any slower the roof wouldn’t have clung on. All the trees around the complex were down.

“There are trees out here I don’t recognize. I don’t know where they came from.”

She was going to attempt to drive into our neighborhood, The Cove, and check on dad. This would prove impossible, as the Cove has (had) a dense canopy of trees, which were now largely lying across houses and roads, bringing power lines down with them.

Audrey managed to drive in as far as was possible, with a few companions, allowed this far by the police only because she works for the City. They then left the SUV and hiked in, over 1.5 miles, over trees, branches, debris, and power lines. They finally made it to our little cul-de-sac that juts into the bay. My dad was ok, though perhaps a little shell-shocked. The same went for Simon, his German shepherd.

Two trees were down on the house, but the metal roof installed a couple of decades ago stood up to them. Two more were down on the covered carport. Many more trees were down in the yard, including the big oak out front that everyone loved.

Our house had taken much less damage than most of our neighbors, many of them missing portions of their roof, or trees protruding through them.

My dad couldn’t make the hike out, so my sister had to find an operable boat the next day, my dad’s birthday, and negotiate all the floating debris to get to the back of the house. She got Sam out, and Simon too. The next day they all drove up to Columbus. It was obvious that recovery in Panama City was going to be a long time coming.

The Drive to Panama City

I managed to make my delayed trip to PC on the 16th. My sister and her husband had returned, since she works for the City, but they left their two-year-old daughter (Annabelle - her birthday had been on the 12th) with my parents in Columbus, since their house was still lacking both water and power. The bed of my truck was full of pallets of bottled water, canned food, gas tanks, and a generator.

I started seeing downed trees as soon as I’d made it a few miles west of Tallahassee on State Road 20. Thirty miles farther, I passed through Bristol and then Blountstown, the sibling settlements that bracket opposite banks of the Apalachicola River in different time zones.

The damage was now immense, and I was still more than 50 miles from home.

Tents filled the courthouse parking lots and parks of these little towns. Mobile command units and service vehicles emblazoned with logos from Central and South Florida jurisdictions were parked all around. Bedraggled citizens stood around looking dazed.

From Blountstown I turned south onto SR 71. My plan was to head west again from Wewahitchka (Wewa, for short) and enter Panama City using SR 21, thus entirely avoiding the Highway 231 from Interstate 10, which I’d heard could take hours due to convoys of utility trucks entering the area.

On SR 71, I first saw destruction on a truly epic scale. There were vast swaths of pine forest where it looked like 75% of the trees were snapped about 15 to 20 feet up their trunks, all laying down in the same direction.

This must have been right where the eye passed over, because things actually improved further south in Wewa. The beautiful old live oaks of Lake Alice Park seemed to be mostly intact.

Callaway, the town on the east side of Panama City, truly looked like a war zone. It was reminiscent of images of a place that had been heavily shelled, like Grozny. Not a single structure was undamaged, and many were completely destroyed.

I soon moved into The Cove. Structures seemed to have fared better, but so so many big gorgeous trees were down. Those blocking roads had already been dismembered and put into huge piles to allow passage.

The trees that made The Cove the undisputed “most beautiful” neighborhood in Bay County – gone.

Despite an urge to see it for myself, I did not even try to visit Mexico Beach, or more accurately the stretch of Gulf-front formerly known as Mexico Beach. I doubt it would have even been possible. The small, largely working-class beach town was basically wiped from the map – a complete loss.

There were however, some notable exceptions. Anyone who watched any news coverage probably saw the image of a newly constructed beach house standing by itself on its piers, seemingly undamaged, while surrounded by a quagmire of strewn debris composed of less sturdy structures. This is the Sand Palace of Mexico Beach (look it up – it has its own Facebook page).

The owners of the house have done many interviews, but they remain coy about its cost. The architect however, has commented that construction to that standard is double the cost per square foot of simply building to code.

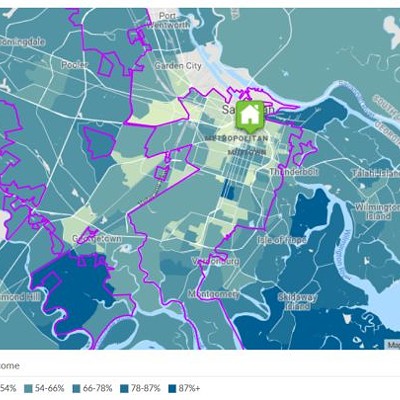

So, why is this an “Urbanist View” column? Because Mexico Beach and Panama City could have been Tybee Island and Savannah. That was in the back of my mind the entire time I was there.

The Cove is so similar to some of Savannah’s waterfront neighborhoods that one might have trouble distinguishing the two from Google Maps street views, at least before the hurricane.

If Chatham County’s recent brushes with disaster brought by hurricanes Irma and Matthew were not enough, then images from the aftermath of Hurricane Michael should be.

Unfortunately, with everything else going on in the country, and the fact that Panama City is not Houston or New Orleans, these images have left the mainstream media all too soon.

Look them up.

Hurricanes are getting worse. We need to think hard about what we can do to prepare Savannah, Tybee, and the rest of Chatham County for its own “big one.”