HAVE YOU heard that the Savannah National Historic Landmark District (SNHLD) is threatened?

That’s the word on the street. But, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

The National Park Service (NPS) commissioned and received an “Integrity and Condition Assessment” of the SNHLD that clocks in at over 200 pages (though the meat is contained in the first 60, so don’t let that scare you too much).

Lucky for you, I have read the whole report, attended both public forums that were held last week, and done a little digging of my own, so that I can try to untangle it all for the readers of Connect.

Let’s start with the use of the word “threatened” and work backwards.

Dr. Turkiya Lowe of the NPS began both recent public forums hosted by the Metropolitan Planning Commission (MPC) by stressing that the designation of the SNHLD is in no way in jeopardy at this time.

The NPS uses the word “threatened” in a very particular way, and it has not even been applied yet.

The purpose of the assessment, which is open for public comments, was to recommend one of four “condition categories” to be applied to the SNHLD. In the conclusion (pg. 62) it is recommended that category be “Threatened (Priority 1)”.

However, to reiterate, this change has not been made, but recommended by the authors of this recent assessment.

So, next question: Why is the SNHLD perhaps “threatened?”

First of all, the aspect of the SNHLD that the assessment is attempting to measure, the one that affects its official status, is its “integrity,” or “a measure of health... ...in terms of its ability to convey the significance that lead to its designation.”

Ah, now we are getting somewhere. So, what is the significance that lead to the designation of the SNHLD?

This brings us to the “original sin” in the creation of the Savannah National Historic Landmark District in 1966 – it was done by decree of the Secretary of the Interior, without nomination, and without documentation.

He just did it. The value of downtown Savannah was apparently self-evident. Justification for the designation came later, in 1969, when a nomination was registered retroactively.

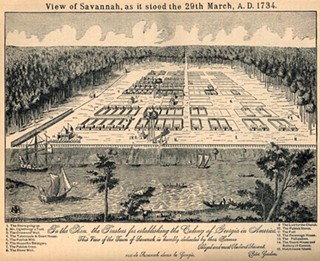

In these 1969 forms (included in Appendix A of the NPS assessment) buildings of architectural value are described, en masse, but in the most salient section, the “Statement of Significance,” the focus is on The Oglethorpe Plan itself:

“Savannah is unusual because of its physical plan. James Edward Oglethorpe, founder of the colony of Georgia, was responsible for this innovation in urban design.”

This section goes on to describe The Plan in more detail, without ever mentioning the architecture that now fills it.

Later, the nomination was updated and expanded in 1977. Whereas the category of designation in the 1969 document had only been “district” — now both “district” and “building(s)” are included.

In the description section of the 1977 nomination, there is a wonderful quote:

“While Savannah does possess a number of very distinguished buildings, and while it has certainly played its role in American history, the real meaning of this area lies in something else. It lies in the wholeness of the place, in the rational nature of the rhythmic placement of streets, buildings, and open areas, and it lies in the great variety of spatial experience throughout the fabric of the district.”

This last sentence is a wonderful and succinct description of what urban design itself is, which I sometimes have trouble putting into words. From now on I will just steal these. In essence, the significance of the SNHLD is in its illustration of what good urban design should be.

But just a page later, seeds of conflict are planted in the updated “Statement of Significance”:

“Savannah survives today as an essentially nineteenth century collection of buildings, built upon Oglethorpe’s eighteenth century plan, a truly superlative urban environment.”

The conflict is between the relative significance of The Plan, and the old structures that inhabit that plan. The Plan, the core of the 1969 nomination, now seems to have been demoted.

The trees are beginning to obscure the view of the forest.

Indeed, whereas in the 1969 nomination form “Urban Design” is offered with its own box, and checked, as one of the Areas of Significance, in the 1977 update “Town Planning” must be inserted at the end under an “Other” box. The forms themselves seem to be biased...

A 1985 update to the nomination is entirely absorbed with issues of architectural history, asking that the “Period of Significance” for the buildings within the District be extended to 1934. The Plan only receives a passing mention.

However, in the current NPS assessment, the importance of The Plan is once again given top billing:

“The assessment team and the majority of the survey respondents agreed that the Savannah Town Plan was the defining feature of the SNHLD.” (page 61)

But again, seeds of conflict are again planted in a following sentence:

“The density and scale of historic architecture from the period of significance within that plan was the second most important character-defining feature.”

Here, I think, is the crux of the conflict.

If you focus on the secondary Area of Significance — historic architectural value — you likely believe that for this significance to be best conveyed, it must not be intruded upon by contemporary infill.

“Integrity” to you means being surrounded by all old stuff, or at least all old-looking stuff. Therefore, anything new, no matter how well done, is a detraction if it does not look and feel historic.

However, this interferes with the conveyance of the primary Area of Significance: The Plan. For it to best display its significance, it must be allowed to accept contemporary additions, and illustrate that though laid out in 1733, The Plan is still relevant now.

But in reading the NPS assessment, there is a clear bias against anything new, even when well designed and constructed.

This is exemplified by the assessment’s treatment of the Jepson Center. In the historical narrative of Chapter 2, the Jepson is called a success of the design review process, which “produced a context-sensitive building, responding to the massing and scale of neighboring buildings on the square.”

However, in Chapter 4: Assessment Results, the Jepson is included as a detraction from Telfair Square:

“The areas south and east of the of the square contain a high degree of non-historic infill development, most notably, the 1985 Juliette Gordon Low Federal Complex on the eastern trust lots, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers federal office building on the southeast corner, and the contemporary Jepson Center for the Arts building on the southwest corner.”

Non-historic infill just can’t win. Even when lauded as a “success” it later gets lumped in with the infamous bathroom buildings.

If you see all contemporary infill as a detraction, and there is obviously contemporary infill happening within and adjacent to the SNHLD, then it is a foregone conclusion that you will recommend that the District be categorized as “threatened”. This is simply wrong-headed.

I will turn here to the words of beloved, now-passed Georgia Tech professor Doug Allen on the Oglethorpe Plan:

It is this network of dimensions, here, that allowed futures that could not possibly have been predicted by the Trustees or by Oglethorpe or by anyone in 1733, to actually develop in the nineteenth century when the city really began to grow.

This is the significance of it. This is the obligation of the urban designer – to accommodate futures that we cannot predict. It is remarkable, the number of building types and land uses that can actually be accommodated within this hierarchy of dimensions.

Real history is not made by preserving old buildings, or by freezing the present into an ossified version of the past. Real history is made when each successive generation, subject to their own condition, can write their own story into a place. The stability of the public frame (in this case, the Oglethorpe Plan) allows the representation of the present to fluctuate according to its own needs, while assuring continuity between past and future.

A wider coalition against actual threats can be built, but not if preservationists insist on painting all contemporary infill as a threat.

The Plan comes first — the oldest and the newest documents about the SNHLD agree on this.

And if you understand The Plan’s true significance, that means allowing it to be occupied in new ways.

If that can be agreed upon, then it will be easier to see that contemporary infill is context-sensitive and aesthetically pleasing, and that true threats (like the proposed new Tomochichi Courthouse extension) can be opposed, and existing mistakes (like the Civic Center complex) can be remedied.

To read the NPS assessment for yourself, and leave your own comments, go to: https://go.nps.gov/savannah

To listen to Doug Allen’s lectures on the history of urban form, including his lecture on Savannah, please look up the Doug Allen Institute on YouTube.