OH MY heavens, y’all, we’re so lucky to live here.

That’s what the nice lady from Michigan told me breathily as we chatted in line at the Savannah Book Festival last Saturday. Betty had traveled thousands of miles in horrendous weather to spend time and money in our lovely city, and she and her best friend, Karen, were having a ball.

They honest-to-God squealed when they found out I was a local, peppering me with questions about where they should eat lunch and whether they ought to take home a few clumps of Spanish moss in their suitcase.

Naturally, I turned up the Hostess City charm, marking up their map and recommending they leave the moss alone unless they wanted to be scratchin’ themselves silly for the rest of their stay.

I may have laid on the Southern accent a little thick, but in the sparkling sunshine of Telfair Square, it didn’t feel like an act.

I love Savannah, and I love sharing it with others. Most of the time.

Of course, there are other moments when residing in a wildly popular tourist destination makes a person cranky, like when you’ve been searching for a parking spot for 45 minutes and now you’re stuck idling behind a horse-drawn carriage as a gaggle of Girl Scouts takes 10,000 Instagrams of the Mercer Williams House.

Or when a bachelor party rents the Airbnb next door and you’re up ‘til 4 a.m. listening to the groom puke in the azaleas. Or watching another 12-story corporate monstrosity gobbling up downtown parking places and views of the sky.

While it’s wonderful to live where so many people want to visit, it definitely has its share of headaches.

But Betty and the other purported 12 million visitors a year are an indubitable anchor our local economy, and their $2.6 billion of annual direct spending revenue buys a lot of ibuprofen. Tourism is also the single largest employment sector for the region, and those new hotels will create thousands more jobs—though not everyone believes that to be beneficial in the long run. (More on that in a bit.)

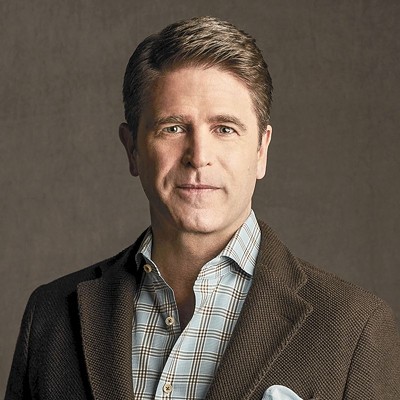

It’s a tricky business, this balancing act of maintaining a good quality of life and showing our guests a good time. And we’re certainly not alone, promises award-winning journalist Elizabeth Becker. In her bestselling Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism, she examines the $6.5 trillion global industry and how other hotspots handle the inevitable issues of oversaturation, regulation and degradation. According to her, Savannah is actually doing a pretty decent job.

Becker gave a series of well-attended public talks last week, regaling diverse audiences from the grassroots Emergent Savannah to the tonier Downtown Neighborhood Association with her favorable assessments: First of all, we are undeniably gorgeous. Also, our short-term vacation rental ordinance may not be perfect, but we’re ahead of the game in that at least we have one. Most importantly, we know how to say “NO” to bad ideas.

“I’ve not found another city that was so against cruise ships,” she said of our kibosh on a 2013 proposal. “I mean, look at the mess Charleston made. It’s rare that a city learns from other cities’ mistakes.”

(I know y’all are grinning right now; we love it when we’re compared favorably against Charleston.)

Becker admonished us to conduct a saturation study lest we end up like Venice, where vacation rentals have swallowed the ancient real estate market, leaving only 60,000 permanent residents in a fragile city that hosts 24 million visitors a year.

In conversation, she also touched on the challenge of incorporating Savannah’s African American and slave history into the metanarrative of the city. (That effort is a focus of the recent formation of the Urban Savannah Chamber of Commerce and the African American Tourism Council.)

“The most important questions going forward are, ‘who are you?’ and ‘where do you want to go?’ I’m not sure you’ve figured it out yet,” she mused.

We welcomed Becker as an enlightened guru with intimate knowledge of parts of the world most of us will never see (she counts Phnom Penh, where she was one of the only journalists granted an audience with Cambodian dictator Pol Pot, as a spiritual home,) but it’s important to note that her ideas aren’t completely foreign to us.

When developing the city’s Dept. of Tourism Management and Ambassadorship in 2014, city staff passed around Overbooked as its inspiration for pro-active policies.

“We recognize that we are in a dynamic environment and must be flexible and make changes when needed to protect neighborhood integrity while sustaining the industry,” says director Bridget Lidy. “We need to talk about the issues impacting our community and develop strategies to address them.”

The hottest issue at the banquet table is is how the hospitality industry contributes to a perpetually subpar economic climate for many of its workers. According to some reports, about half of the people with 25,000 hotel and service-related jobs make an average of $8.60 an hour—less than $16,000 a year. Federal guidelines cite a family of four that earns less $24,300 as below the poverty level.

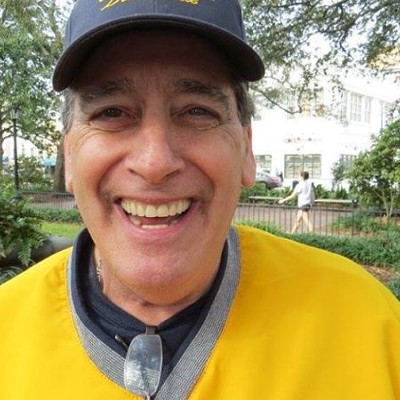

“These are poverty wages,” rails former Chatham County Commissioner John McMasters, who has been an outspoken proponent of wage reform in our local hospitality sector.

“Each new hotel built will only enlarge our poverty level, so the obvious conclusion is to either stop building hotels or find a way to raise wages. We are digging the poverty hole deeper and deeper while our quality of life degrades from the onslaught of increasing tourism.”

McMasters has proposed to raise hospitality wages two dollars an hour, an idea fast gaining populist support on his Facebook page, though the business sector scoffs at such government-mandated sanctions.

Since we’re about as likely to stop building hotels as we are to stop frying shrimp, an increase in 10 percent of the city’s paychecks could and would dramatically cut the city’s stubborn 28 percent poverty rate—and byproxy, reduce crime motivated by generational poverty.

From her world-sized view, Becker suggests the way for workers to advocate for better compensation is to organize. But that’s a difficult edict, as just breathing the word “union” around here gets people all huffy. Georgia’s despotic “right to work” laws keep unions weak anyway, and state legislators voted down a minimum wage increase last year.

Can Savannah create a more livable wage for its hospitality workers on its own? It seems to be trying. In December, the City introduced the West Downtown Urban Redevelopment Plan, which gives incentives to downtown businesses to hire from the poorest neighborhoods and pay at least 25 percent above the $8.60 average—an increase along the same numbers as McMasters’ plan.

Participation hasn’t quite caught on with big box boys, and perhaps city-directed negotiations among all the stakeholders can give the program momentum.

Others maintain that tourism’s low-paying gigs are an unfortunate but necessary evil.

“Look, this is the service industry, and a lot of its jobs are for housekeepers and dishwashers,” says Tourism Leadership Council director Michael Owens. “But those jobs can lead to a true and real career path if someone wants to work.”

Owens advocates for better training so that more minimum wage workers can move up the ladder, citing the example of the current general manager of a prominent hotel franchise who grew up in local Section 8 housing and started work at 16 in the back of the kitchen.

“Every industry has to have bottom rungs. If you want to change how people move up, our focus as a community must be on education and skills,” he says.

So how do we empower a capable, enthusiastic workforce while recognizing the reality of the free market?

If Paris can figure out how to shuttle 7 million people a year up and down the Eiffel Tower, surely our council can draft regulations that prevent the corporate takeover of our tiny downtown without sending the rabid capitalists into a tizzy?

Becker assures that it is possible to accommodate travel’s big boom without biting the hand that feeds us.

“The key to good tourism is to do your planning for the people who live there,” she writes.

Speaking of the bigger picture: For all of her whirlwind engagements around town, after three days in Savannah Becker had yet to enjoy much of the city outside of her Gordon Street bed-and-breakfast. I tagged along as Kevin Klinkenberg of the Savannah Renewal and Development Authority chauffeured her in a wide circle through the historic district and the contrasting neighborhoods, presenting a far more complete tableau than most tourists ever see.

Slicing between blocks of fancy townhomes and blighted bungalows, we discussed how Slowvannah’s sleepy urban renewal efforts may have worked in our favor as it inadvertently preserved places culturally-rich areas like the historic Cuyler-Brownsville neighborhood.

Klinkenberg and the SDRA are working to invigorate these once-thriving commercial districts and include them in the spoils of Savannah’s prosperity.

Still, some of our future plans seem questionable when seen from an outsider’s perspective. I have never experienced a longer or more awkward car ride than the detour taken to the site of the proposed arena site on the blighted west side.

“Wow, this isn’t anywhere near your tourist corridor, is it?” murmured Becker.

We were all glad to finally ditch the car and walk through Forsyth Park, where the sublime afternoon had enticed picnickers and basketball players and hammock dwellers out to our jewel of common greenspace.

“It’s so beautiful and alive here,” she marveled, taking in a thatch of candy-colored azaleas.

It was so gratifying to watch a world traveler like Becker become enchanted by Savannah, and I’d like to think we made as important an impression on her as she did on us. Like every other tourist, she’s left a bed of used linens behind, but her queries continue to ring on:

Who are we, Savannah? Where do we want to go?

I spend a lot of time trying to wrap my head around the complex, diverse nature of that first question, and I still don’t know.

But I’ll tell y’all, as I sit on a shadow-dappled bench in my favorite moss-draped square listening to the early morning buzz of a city readying for work and play, there’s only one way to answer the latter:

Nowhere but here.