OF ALL the equipment in the kitchen, the chef’s knife is the most personal and useful tool you’ll ever want for.

Its general shape hasn’t changed since the Middle Ages. The standard European design was meant to be as utilitarian as possible to slice, dice, and butcher. The chef/cook’s knife cost a lot of money back then as is true today, and so had to perform many tasks well to warrant the expense.

It used to be that carbon steel knives were the ones to get. They could be easily sharpened to a razor edge. The best Japanese knives still are but they are prone to rust if you are not meticulous in their care.

Then came stainless steel knives. They kept an edge longer then the softer carbon steel blades and didn’t rust but they were heavy and brittle. When they go dull they have to be professionally sharpened, unless you happen to own a belt grinder.

In more recent times we have the best of both worlds in high carbon stainless steel blades. The worst is the stamped “Never Sharp” knives sold in a block to unsuspecting newlyweds, college students, and thrifty minded home cooks.

Relax, if bludgeoning a chicken or two with some vegetables works for you, then save your money. Buyer beware, even the good brands sell these knife-like substitutes.

As far as quality goes, it comes at a price. For a good chef knife, be prepared to drop a minimum of $120. There are the different weights, length and styles to consider for your perfect knife but much of that is personal taste.

As a general rule, a good quality knife is balanced between the blade and handle. This is why you hold the knife in the middle to keep in full balanced control, more like shaking hands and less like auditioning for the next Psycho movie.

First rule in knife skills is always know where the blade is, and your fingers. Being able to count to ten after cutting up a carrot is not only impressive but somehow reassuring to your guests and employers.

In the professional role, we tend to go for the 10-inch bladed chef’s knife as our work horse. It’s big enough to take on most tasks in the kitchen without having to change knives too often.

I recommend for the home cook three knives: the 8-10- inch chef’s knife, a 3-inch paring knife and a 6-inch boning knife, plus a 10-12 inch Steel (more on that in a moment). Those are really all you need to accomplish the lion’s share of knife work in most kitchens.

I recommend buying them individually and not in a set or block. The sets sell you what they want to sell not necessarily what you need.

On the TV and in cookbooks they’ll show you how to hold the food with your curled fingertips as the side of the knife blade brushes against your fore knuckles. You make a sawing motion with your blade and move the food into the knives’ path.

Feel awkward and unnatural? Good, you’re doing it right, as long as you keep your finger tips out of the way.

After practice this will feel more natural but it takes time. Speed will come with that time, don’t force it. Remember how good it will feel being able to count to ten.

With speed comes better uniformity in your cuts, for some reason going too slowly people tend to over think the cut. You’re using a sawing motion to optimize the cutting force of the knife. A straight-edge knife, on a microscopic level is serrated with many tiny teeth, just like a saw.

This brings me to a very misunderstood tool, The Steel. It’s also known as a honing rod and a sharpening steel.

Let me be perfectly clear, a Steel does not sharpen. If your knife is dull, no matter how Harry Potter you get, the steel doesn’t sharpen!

Its function is to hone the edge of the knife. What that means is that through the course of usage those tiny little teeth have come out of alignment and the edge isn’t as effective.

Running both sides of the knife edge at a 15-20 degree angle on a steel say 8 to 10 times each side realigns the teeth, sometimes called bringing up the edge.

To better maintain the edge of your knife, it’s a good practice to get into steeling your knife before you use it.

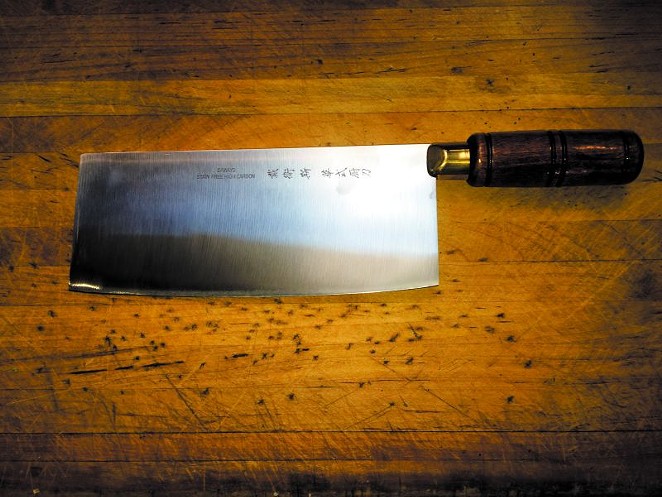

As a starter knife let me suggest to you the practical multitasker of the Far East. I speak of the Chinese Chef Knife.

Yes, it looks like a meat cleaver. Once you get over the intimidation factor you’ll appreciate its utilitarian design. It’s easy to learn knife skills with its deep blade. It’s simple to maintain and affordable, $20+.

The wide blade was designed to crush garlic/ginger and scoop up the chopped food and convey it to your hot pan. The handle was designed to grind spices in a mortar. Its spade-like blade is perfect for finely chopping fresh herbs or mincing onions.

The takeaway here is for you to discover what works better for you and to question what you really need. I suggested getting a boning knife but if you never break down whole chickens or other butchering projects, you can save your money.

A decent paring knife can do double duty for the small tasks of the butchering you will do, like trimming silver skin or cutting away excess fat.

I’ve also suggested getting a steel to better maintain the knife’s edge. While these are not expensive, they’re like home exercise equipment. You may have all the best intentions but if it’s just sitting in a drawer only to be brought out for show on Thanksgiving, save your money.

As more and more people are getting into cooking for health, creativity, and fun, its easy to see why many people hate to cook. It can easily be a frustrating and unrewarding experience in the kitchen as you slowly press the life out of that poor Vidalia in a fog of tears.

I well remember those days. A sharp knife would have helped.