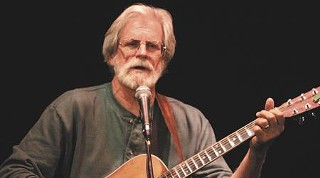

Jack Williams has been many things, all of them musical. He played lute in a renaissance group, trumpet in a hipster jazz combo, and guitar in too many rock ‘n’ roll bands to remember. He rowed the boat ashore with a Kingston Trio-esque folk outfit.

He’s been a professional musician for more than 50 years.

Since 1997, however, the South Carolina native has been a mainstay on the country’s exceedingly healthy folk music circuit, as a solo performer. A masterful finger-picking acoustic guitarist, Williams has a clear, expressive voice, and he’s also a strong songwriter, and a storyteller who’ll bust your gut if you’re not careful.

Saturday’s Jack Williams concert, at First Presbyterian Church, is a presentation of the Savannah Folk Music Society, which likes its shows smoke-free, alcohol-free and noise-free; these concerts are for people who just want to hear good tunes from a top-of-the-line player.

Williams fits the bill to a tee. He and his wife, who make their home in northwest Arkansas, average about 70,000 miles on the car every year, ferrying him from one gig to another (he plays 48 states per annum) in concert halls, at folk festivals and even at house parties. Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul & Mary fame) calls him “The best guitar player I’ve ever heard.”

(Sidebar: Williams and his folkie cohorts were regular performers at the Nite Flite Café, Savannah’s legendary folk club, throughout most of the 1960s.)

He makes a pretty good living this way, and nobody ever leaves disappointed. With seven CDs available through his Web site, and occasional session dates in Nashville, Williams has a sweet career – even better, he says, because it’s all being done on his own terms.

Instead of the traveling lifestyle, couldn’t you just plant yourself in Nashville, make records and play sessions?

Jack Williams: No, that would make me sick to my stomach. Nashville would end me – the commercial music world has no appeal to me at all. Commercial music has no appeal to me any more. I used to like some of it, in my younger days, but I’ve parted ways with it. And now I love to be involved in the folk community, in places where people are basically playing because they love to play, and they’re writing and performing music that matters more to them than just the dollar.

Was there a specific thing that caused you to chuck it all in and go with strictly solo folk music?

Jack Williams: It was a combination of things. From ’58 to ’88, my career involved other musicians and ensembles. In 1968, I started playing some solo gigs and pretty soon I had concurrent careers. Somewhere between ’88 and ’95, I got a whiff that there was a circuit that was basically non-commercial, no bars, no restaurant sort of deals. It was the U.S. folk community.

In 1995, I went to Portland, Oregon, for my first-ever Folk Alliance conference, with my then-partner Mickey Newbury, the great Texas singer/songwriter, who’s dead and gone now. There was Tom Paxton and Pete Seeger, and Mickey and I both agreed that we thought they were both dead. We didn’t know; we were just locked into another world.

But that pretty much changed me. I haven’t missed a Folk Alliance conference since 1997.

What about songwriting? Did that change too?

Jack Williams: I had been writing music since 1970, but there was always something compelling me to write for my audience, to try to please everybody and make your good living thereby. But I always had the drive to write for myself, about my own observations, interests and experiences. Around the late ‘90s, I began to write songs that mattered to me – and whenever I played them in front of folk audiences, that was the stuff they liked the best. If I played them in front of the leftover bar audiences, they paid no attention at all.

I understand you knew Harry Nilsson, one of the great pop vocalists of our time. Tell me the story?

Jack Williams: It was a wonderful fluke. I had a great trio – acoustic guitar, bass, drums and percussion. We were the house band in a Holiday Inn bar in Frisco, Colo., in 1973. The drummer was a 450-pound black guy from Missouri named Bummer. Arch, the bass player, was a skinny white guy. We were Jack Arch & Bummer.

One Wednesday, we had a dud of a night, there was nobody there. We were up there just making up stuff; we had great three-part harmony, we could improvise anything. The doors opened up and three people – a man and two women - came in, carrying their dinners from the dining room to listen to us. They kept requesting songs, they cheered us on, they loved everything we did.

I didn’t recognize the guy, but later he said to me “How would you guys like to come out to Los Angeles and put an album together?” I said sure, right. We’ll talk after the gig. Sure.

That was Harry?

Jack Williams: I told Arch and he said “Who is the guy?” I said his name is Harry Nilsson. And Arch almost fell off the stool.

That night, Harry and his wife-to-be, Una, came out to my cabin. We called all our friends, and about 20 of us got over there. And the only people left awake playing music at dawn were Harry and me.

So did you make the record?

Jack Williams: We cut seven demos for Harry to take to the president of RCA. The message was that everything was go, but it was 1973, when the music business was in a mess. Everything was falling apart.

Harry and I stayed in touch over the years – I would send him songs – but he eventually lost his deal with RCA, unfortunately mostly because he blew out his nose with cocaine.

That was just a brief period, but it was very important for me to get to hang out with someone with a voice like that.

On Pussy Cats, the album Harry made in ’74 with John Lennon, he used my slow arrangement of “Save the Last Dance For Me.”

Where did you learn to pick like that? Who were your influences?

Jack Williams: They weren’t guitar players. I don’t care much for guitar music – if I’m going to hear melodies, I’d rather hear cello, viola, violin, oboe, bassoon. A guitar is a wonderful thing for songwriting and the simple folk approach of presenting a song in its naked aura.

I was a jazz trumpet player from the ‘50s into the ‘60s, and I thought that was what I was going to do. Rock ‘n’ roll came along, and I did a little of that. I even had a band that went up to play beatnik coffeehouses in Seattle – I’d be playing trumpet and reading beatnik poetry during the breaks – Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg.

I spent nine years at the University of Georgia, studying composition. I loved to write. I love strings and brass, percussion and voice. So whenever I played the guitar, whatever aesthetic guided me in my jazz, classical and rock days, I tried to duplicate it in my guitar.

Guitarists ask me “Where did you get that great voicing of that chord?” And I say it’s from my jazz arrangements, or the way the bass moved in a classical piece. So I didn’t learn from listening to guitar players – I did learn some rock licks – but as far as the way I play acoustic, finger-style, it was more akin to classical and jazz. I started finger-picking when I heard Stephen Stills play “Helplessly Hoping” – I thought, I can do this. And I had it down in about 10 minutes.

Jack Williams

Where: First Presbyterian Church, 520 E. Washington Ave.

When: 8 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 15

Tickets: $10 public, $8 Savannah Folk Music Society members, $5 students and children

Online: www.savannahfolk.org

Artist Web site: www.jackwilliamsmusic.com