TO THOSE who have heard it before, the sound is unmistakable: Rinka-dadink-dink-da-dink-dink-dink!

Slapped out sharply on a djembe—a round drum played with the hands—the clipped notes signal that the West African rhythm kuku is about to begin.

It also means you’d best be ready to dance: Kuku means celebration, and it’s hard to keep your feet and hips still as the drummers launch into its full-speed glory. Especially when it’s accompanied by the ka-doon-chuk-chuk! booming from a barrel-shaped dundun drum under mallets the size of hammers.

The dances and drum rhythms of West Africa have been moving people for thousands of years, and the tradition’s simple choreography and joyful spirit continue to find their way around the world. In many U.S. cities, master teachers from Guinea, Ghana and Senegal make their livings leading classes for diverse audiences who are seeking a way to connect with their communities and their own bodies.

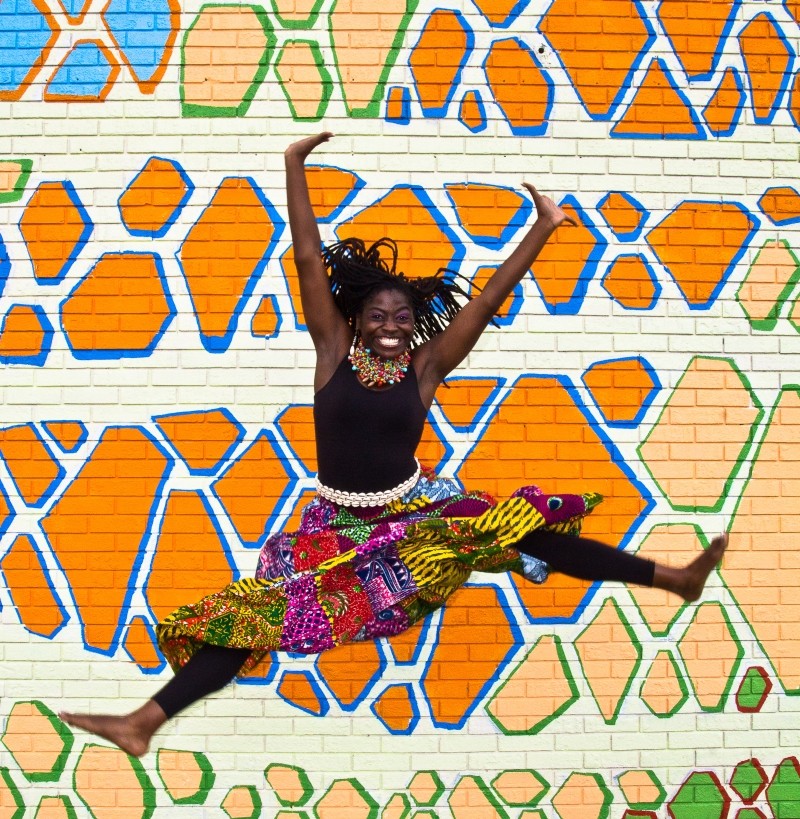

“It’s fun, it’s enjoyable, and anyone can do this,” avows Weslyn “Lady Mahogany” Bowers, a Savannah dance teacher, activist and radio personality at 94.1 “The Beat” WQBT.

“African dance is for everybody—black, white, young, old. It’s about gathering and celebrating life.”

Mahogany hopes to see a colorful cross section of Savannah’s community when she hosts a West African Dance Workshop this Sunday, Sept. 28 at the W.W. Law Center on Savannah’s eastside.

Essential to any successful West African dance class is the presence of the aforementioned live drumming. At Sunday’s workshop, longtime local rhythmic presence Abu Majied Major and his son, Yusuf, will lead on djembe and dundun. Major—who goes by Majied—would like to introduce more young people to the benefits of playing African rhythms.

“When you drum, it’s not only about the syncopation,” describes Majied, who has studied with renowned African drummer Roland Jackson and performs regularly at area Gullah festivals.

“There are all of these other things: You learn how to be social. You learn timing. You learn how to observe.”

Most importantly, he says, African drumming fosters the sense of harmony so many human beings are seeking in a fractured world.

“It doesn’t just teach unity—you feel it.”

Savannah’s African-American heritage and vibrant creative community are fertile ground for a grand drum and dance gathering, and the city’s history as one of America’s busiest posts of the African slave trade holds a particular significance. Some suggest that dancing and drumming together can be a way to mitigate and process the painful circumstances that brought the rhythms to these shores in the first place.

“The African history of Savannah is everybody’s history,” reminds Lillian Grant-Baptiste, a consultant, educator and storyteller who can often be found performing at local libraries and festivals.

“These traditions of dancing and drumming took place at weddings, at funerals, for rites of passage. This is more than an art form, it’s a way of life.”

Grant-Baptiste points out that while the Lowcountry’s Gullah communities managed to preserve some African traditions, most enslaved people were unable to pass on the rhythms of their ancestral homeland. Yet she notes that familiar influences can be heard in the ring shouts of black churches and among isolated communities like Harris Neck in McIntosh County, where elders can trace childhood lullabies to a specific village in Sierra Leone.

“In a sense, these rhythms are a path from past to present,” she muses, adding that forms of dance including step, hip hop and even swing all hearken back to Africa.

It’s on this path that Mahogany invites all those who enjoy movement to join her. Part of the powerful faction of young women who made up the Sankofa dance troupe of the 1990s, Mahogany studied with Samba Diallo, a former member of the National Ballet of Côte d’Ivoire who now teaches in Atlanta. (Sankofa Dance Theatre continues to host African dance classes, as does Sankofa alum Muriel Miller at her studio, Abeni Cultural Arts.)

After graduating from Savannah Arts Academy, Mahogany also went on to tour as a backup dancer with Beyoncé and Janet Jackson before coming home to Savannah.

“The whole premise of Sankofa is ‘go back and fetch it,’ meaning returning to the source, to our origins,” she explains.

She professes gratitude to community elders like Grant-Baptiste for instilling the importance of tradition and community, and says it is their work that inspired her to return to her old neighborhood to help a new generation. (Part of the proceeds from Sunday’s workshop will go to Blessings in a Bookbag, the non-profit Mahogany founded to send hungry schoolkids home with food for the weekend.)

“I’m supposed to be the person who stays put,” she affirms, just as a sound bite from kuku’s signature rinka-dink-dink floats past. She begins to sway her hips, cowry shell belt jangling, then catches herself and grins.

“Well, maybe not stay put, but you know what I mean.”