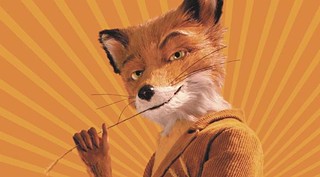

Fantastic Mr. Fox

Whatever is in the water out in Los Angeles is forcing today’s most acclaimed young filmmakers to bring beloved children’s books to the big screen.

First it was Spike Jonze directing an adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, and now it’s Wes Anderson helming a motion picture version of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox. At this rate, can we soon expect Darren Aronofsky to tackle Dr. Seuss’ Hop on Pop and Paul Thomas Anderson to serve up Arlene Mosel’s Tikki Tikki Tembo?

As for Anderson’s stop-motion-animated opus, it’s an improvement over Jonze’s recent live-action effort, even if it falls short of being the new family classic dictated by the advance buzz. The mistake would be in categorizing it as a children’s film, as it largely leaves out the sort of oversized humor found in movies made for the small fry. Instead, its pleasures, including Anderson’s painterly compositions and the A-list vocal cast, seem more likely to win over viewers of voting age and above. George Clooney brings his usual mix of leading-man swagger and character-actor eccentricity to his interpretation of the title character, a newspaper columnist who once promised his wife (a largely wasted Meryl Streep) that he would leave behind his life of danger (i.e. stealing chickens) but instead finds himself being lured back by the prospect of sticking it to a trio of insidious farmers (the leader being voiced by Dumbledore himself, Michael Gambon). Moving to its own laid-back rhythms (an approach sure to cause seat-shuffling from those not on its wavelength), this likable lark functions as a reprieve from the plasticity of most modern ’toon flicks. It may not be fantastic, but it’s good enough.

The Twilight Saga: New Moon

Hollywood’s second foray into the Twilight zone features enough fantasy and romance to satisfy most hardcore devotees of Stephenie Meyer’s vampire saga, but just as many viewers will notice that this is too often a case of the emperor –– or, more specifically, buff teenage boys –– wearing no clothes.

A step down from last year’s box office hit Twilight, New Moon has retained the same screenwriter (Melissa Rosenberg) but opted to switch out directors (The Golden Compass’ Chris Weitz in for Thirteen’s Catherine Hardwicke). Perhaps it’s this changing of the guard that prevents this latest picture from ever maintaining a steady rhythm. After all, Twilight might have been occasionally ripe, but that worked for the material, as Hardwicke instinctively fed into the oversized angst that all too often defines the lives of teenagers wrapped up in their daily melodramas. By comparison, Weitz keeps the proceedings on a low simmer, an emotional oasis only punctuated every once in a while by Bella’s howls as she pines for her one true bloodsucking love.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. In New Moon, vampire Edward Cullen (Robert Pattinson) has decided that it’s too dangerous for his human girlfriend Bella (Kristen Stewart) to be around his kind, so he and his family pack up and leave their Forks, Wash., home, ostensibly for good. Missing her soulmate, Bella shuts down completely, and is only slowly drawn out of her shell by her friend Jacob (Taylor Lautner) –– and by the discovery that Edward appears in ethereal form whenever she’s in danger. Bella repeatedly puts herself at risk - riding motorcycles at daredevil speeds, diving off impossibly high cliffs, gorging on fast–food combos every day for a full month (OK, kidding on that last one) - but soon discovers that an even deadlier option materializes with the return of some vampiric foes. And what’s with those gigantic werewolves stomping through the Pacific Northwest woods?

As before, the whole enterprise is primarily held together by Stewart’s performance, a believable mix of adoration for her man and attitude toward the rest of the world. The plot structure limits Pattinson’s screen time, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing: Less effective than he was in Twilight, here the actor seems bored by the franchise, as if he’s already anxious to try his hand at more mature roles. As Jacob, Lautner projects a wholesome earnestness, even if he’s victim to most of the film’s most risible moments –– I especially chuckled during the scene in which he tends to a cut on Bella’s forehead not by tearing off a swatch of his shirt but by whipping off the entire garment, thus allowing audiences to appreciate his bulging biceps–upon–biceps.

Then again, you can’t say that Weitz doesn’t have his target audience in sight. In my review for Twilight, I wrote that the movie was “a love story first and a vampire tale second.” Given Pattinson’s ascension to pinup star as well as the pack of shirtless hunks filling out this latest film’s supporting cast, it’s safe to amend that statement to read that New Moon is a love story first and a male–model calendar second. The vampire tale has become almost incidental.

Precious: Based on the Novel 'Push' by Sapphire

“Kitchen sink realism” was the term invented to describe a specific type of artistic movement that took place in England in the 1950s and 1960s, and here comes Precious to borrow that expression for a more modern, decidedly Americanized look at life among the lower classes. Adding to the appropriateness of subletting that term is that fact that a good part of this harrowing drama is set in and around the kitchen, as a frying pan to the head and hairy pigs feet to the arteries both take a toll on the well–being of the story’s heroine, 16–year–old Claireece “Precious” Jones (Gabourey Sidibe). Living with her hateful mother (Mo’Nique), a woman who abuses her in every way imaginable, Precious has to contend not only with a disastrous home life but also with the fact that she’s pregnant with her second child, both kids the result of being raped by her own long–gone father. Grossly overweight and largely illiterate, Precious nevertheless harbors a poetic side and can only hope that her life will take a turn for the better. She finally finds some allies in a patient teacher (Paula Patton) and a no–nonsense social worker (Mariah Carey, surprisingly effective), but their encouragement repeatedly gets negated by her mother’s assertions that she’s ugly, unloved and unwanted.

The 2009 release least likely to be mistaken for the “feel–good movie of the year,” Precious is for most of its running time so pessimistic that it threatens to hammer viewers into a fetal position from which they may never emerge. Yet it’s this hard–edged honesty –– a far cry from the chipper, meaningless platitudes on view in many other works –– that earns this film its stripes. Yet its key ingredient is Sidibe, whose excellent performance crucially transforms Precious from a character to be pitied into a person to be admired.

The Blind Side

The Blind Side is typical of the sort of racially aware films Hollywood foists upon middle America, purportedly focusing on a black protagonist but really serving as an example of the goodness of white folks. The only reason this young black boy exists, it seems to hint, is so that a Caucasian woman can feel good about herself. The fact that The Blind Side is based on a true story dispels much of this criticism, although it still would have been nice if writer–director John Lee Hancock had thought to include the character of Michael Oher (Quentin Aaron) into more of his game plan. Instead, he’s a saintly, one–dimensional figure –– although he (like everyone else in the film) seems like the spawn of Satan when compared to Leigh Ann Tuohy (Sandra Bullock), the feisty Southern belle who decides to feed, shelter and eventually adopt this homeless lad after spotting him one dark and stormy night.

Bullock’s a lot of fun to watch in this role, and the movie itself contains enough humor and heartbreak (though next to no dramatic tension) to make it an engaging if undemanding experience. But its true intentions are revealed in its ample self–congratulatory dialogue. “Leigh Anne, you are changing that boy’s life.” “No. [insert dramatic, Oscar–friendly pause here] He’s changing mine.” You can almost see the filmmakers patting themselves on their backs before heading home to their maximum–security Beverly Hills mansions.

2012

The perfect follow–up for those moviegoers who were simply crushed when Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen wrapped up at a too–brief 142 minutes, 2012 contributes another 158 minutes to the cause of wham–bam–thank–you–man cinema. No effect is too preposterous, no sound too deafening, and no cliche too enormous to be left out of the latest end–of–the–world effort from director Roland Emmerich, who there but for the grace of God goes Michael Bay. On balance, I can handle Emmerich’s output better than Bay’s, but it’s clear that the gap between them is shrinking at a rapid clip. Emmerich’s Independence Day and The Day After Tomorrow may have been dopey, but both were carried off with a certain degree of panache, and ID at least gave us the lingering image of the White House being blown to smithereens by invading aliens. In 2012, we see the White House being crushed by a wayward naval vessel, a visual more moronic than iconic.

2012 brushes through the fuzzy science - basically, the sun is responsible for Earth’s impending doom, predicted by the Mayans way back when - in order to devote more of its time to its inane assortment of cardboard characters and the CGI effects that will wow some but fail to move others (they alternate between impressive and obvious). John Cusack is the all–American protagonist, a stock underachiever named Jackson Curtis (not to be confused with Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson) who must rise from Everyman to Superman in order to save not only himself but his fractured family unit (ex–wife, distant son, chipper daughter). There’s also the well–meaning scientist (Chiwetel Ejiofor), the duplicitous politician (Oliver Platt), the self–sacrificing U.S. president (Danny Glover), the conspiracy–theory nut who turns out to be right about everything (Woody Harrelson, whose zealotry was a lot more fun to watch in Zombieland), and so on.

Even “master of disaster” Irwin Allen liked to shake up the status quo in such films as The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, but Emmerich has no imagination: His A–listers live, his support players die. Worse, he subscribes to a rigid ethical code usually reserved for slasher films and fundamentalist diatribes: Likable characters tempted by the flesh suffer mean–spirited ends, as does anyone who dares to stand in the way of traditional family values. Such sermonizing takes a back seat, of course, to the action sequences, which basically seem to run on the same loop: A car (or plane) misses getting crushed by only this much. It’s marginally exciting the first 20 times it happens, less so the subsequent 30 times it’s shown. Then again, practically everything about the picture is lazy and uninspired, making 2012 just one more blockbuster that’s strictly by the numbers.