SCENE: THE GREEN TRUCK PUB. The place is packed. You’d think it was a weekend dinner rush, but it’s mid-afternoon on a Wednesday.

I’m sitting at the bar with a few friends enjoying a draft beer (or three) and warm French fries with aioli.

Outside, it is snowing.

Yes, this was just last week, January 3, 2018. The date that snow—real snow, not a dusting—actually fell on Savannah and stuck. And at the moment of writing this column, it is still sticking in many shaded patches.

As I sat at the bar of the Green Truck amidst the thrum, scanning the crowd and seeing familiar faces, bantering with the staff, my city planning lizard brain was grinding on something.

This is because the weather conditions had created a “natural experiment.”

You usually hear about “natural experiments” in economics. Because economic theory is so wide-ranging and intertwined with human behavior, you can never test theories in clean, controlled laboratory settings as you might in physics with a particle collider.

Instead, you must observe the natural course of events and try to extrapolate from the mess that is real life. But once in a while, something happens in the real world that presents you with a very clear data set, based on a change in a clear variable, that can be compared to the norm—the control. This is the occurrence of a natural experiment.

And the natural experiment that we were gifted with last Wednesday, and somewhat in the days after, was:

What happens in Savannah when the population is deprived of the use of their automobiles?

We were all both participants and observers of this experiment—how did it affect you? Your neighborhood? Your place of work? Was your life completely put on hold by the deprivation of automobiles, or not?

From my limited vantage point atop a bar stool, I was thinking about downtown businesses, and particularly food and beverage establishments.

Given the conditions, could they, should they, stay open for business?

As for his own thoughts on staying open, when I asked him later Green Truck owner Josh Yates replied, “When you realize about 30 people rely on Green Truck as their source of income, you’re very reluctant to cancel work for the day. It’s also really wonderful to provide a place for the community to be together, which really is why my wife (Whitney Shephard Yates) and I opened a restaurant in the first place.”

(Full disclosure: Josh and I sit on the board of the Thomas Square Neighborhood Association together, but I was a patron of his establishment long before we knew one another personally.)

But for most businesses the answer was “no,” despite wants and needs. Some businesses realized it intuitively, others when their lack of staffing and/or customers made it clear after trying to open.

Not so for establishments like the Green Truck. It was open, well-staffed (though short), and booming with business.

Josh confirmed that they did “weekend numbers.” Hell, where else did people have to go?

The hurdles that Green Truck cleared in this auto-deprivation experiment were two-fold:

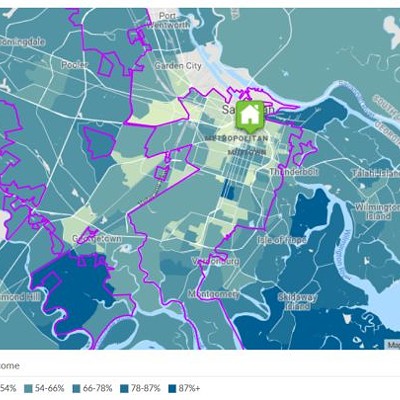

First, it is embedded in a walkable neighborhood, allowing it to be easily accessed without a vehicle, for those lucky enough to live within the “walk-shed” (a term adapted from watershed—an area draining to a certain river, but in this case the area comfortably accessible by walking).

Second, and perhaps more importantly, within the neighborhood there exists a “jobs-housing balance” on a very local scale. That is, a large number of people working at Green Truck actually live close by. I’d venture that this goes for many Starland/Thomas Square businesses, especially of the food and beverage variety.

So, empirically observed in this experiment:

Walkability + jobs-housing balance on a neighborhood scale = resilience in an auto-deprived circumstance.

Resilience in the short-term, at least. This is because Green Truck Pub WAS forced to close, but not because of staffing or customer issues. It had to close mid-afternoon on Thursday because it was running out of supplies, and deliveries would not resume until the next day.

I will now attempt to describe two potential responses to the Green Truck outcome of this natural experiment:

“That’s interesting and all. Congrats, walkability and jobs-housing balance, you allowed a business to stay open one and a half extra days. In the other 12,774 days of the past 35 years we used cars and it didn’t matter. Plus, you were still brought down by a supply chain dependent on automobiles.”

“The staying open 1.5 extra days is not the point. The point is that the ability to stay open under the circumstances demonstrated the existence of qualities that make the neighborhood cohesive and desirable as a place to live, work, and play. Hence, demonstrating why this neighborhood is experiencing the pressures of gentrification, eroding the very jobs-housing balance that was just displayed. Congrats.”

Yes, it is true. Though this is not a part of my Gentrification Series (trademarked caps), jobs-housing balance is of course related. Josh Yates stated that less of his staff now lives close by than they used to, due to rising rents.

In idealistic city planning circles jobs-housing balance is an elusive goal (in fact, it is argued as to whether or not it should be a goal), valued for two main reasons: it lessens car dependence, hopefully leading to less car use, hopefully leading to environmental benefits; and it is a measure of social justice—it would be nice if every neighborhood contained housing choices affordable to those working the jobs that also exist in that neighborhood.

If this has all seemed a belabored discussion of conditions that will probably never repeat themselves, think about this. Yes, this was an acute condition. All we had to do is wait a few days for the snow and ice to melt, and we could then all use our cars again. Problem solved.

However, right now the two greatest powers in the region that exports most of the oil to the world, Saudi Arabia (Team Sunni) and Iran (Team Shi’ite) are involved in a proxy war in Yemen.

If this war goes from proxy to direct, the body of water that lies between them, The Persian/Arabian Gulf (depending on your team) would likely be very unsafe for shipping all that oil, and prices would spike.

Yes, we frack a lot of our own oil now, but it is still a part of the global market, and its price would go up. Then, dear readers, the matters of walkability and jobs-housing balance might become a very un-academic and chronic concern.

But on a lighter note, before the memories of it fade, reflect upon your part in this natural experiment that we were all given part in.

Did you enjoy your Snow Day? Was it because you were able to function despite being deprived of vehicle use? Was it because you hate your commute and simply didn’t have to make it?

Was it instead because you hate your boss and co-workers and didn’t have to see them? Was it because you got to binge the new season of “Black Mirror”?

Whatever the answers, maybe they will give you some new insights, and allow you to craft some new goals towards a happier future lifestyle. Happy New Year.