RAPE KITS are backing up on a monthly basis at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI). With a two-year trend of approximately 300 new rape kits submitted per month — but staffing to only process 100 of them — the growing backlog is becoming unmanageable, and causing many victims of rape to have little faith in the system.

Despite exceeding the capacity of their current scientists, GBI Director Vic Reynolds is requesting a budget cut that will eliminate 11 scientists and two lab techs.

Gov. Brian Kemp has required all state agencies to cut their current budget by 4% and their 2021 fiscal year budget by 6%.

When pressed by members of the Appropriations Committee last week, Deputy Director of the GBI Crime Laboratory, Cleveland Miles, disagreed with his own boss.

He stated in testimony that the GBI needs to add 10 new scientists, specifically to address the mounting backlog of rape kits, and not cut positions.

Considering that many rape kits do not get tested, and that the ones that do take an average of 312 days from receiving to completion, Gov. Kemp’s and Director Reynolds’ proposal to cut scientist and lab tech positions threatens to take an already out-of-hand situation and make it that much worse.

Reynolds’ numbers don’t seem to add up either. He reports that there was a backlog of 768 rape kits. This seems an unlikely number since the previous month, there were 1,540 rape kits in the custody of GBI crime labs — especially when you factor in the additional new kits submitted per month.

Given their own data, it seems improbable that the GBI could have tested that many kits in a month, leaving estimates that approximately 1,000 rape kits were excluded from the total that Reynolds presented to Georgia lawmakers.

Dashed hope

In 2016, when SB 304 passed, it was greeted with fanfare, featured by Samantha Bee with Schoolhouse Rock flare.

The new law, ushered in by Rep. Scott Holcomb (D-81), required that hospitals turn rape kits over to the police within four days, and that police transfer them to the GBI within 30 days.

Holcomb says, “I was aware of the national issue in 2015 and that’s when I first filed the legislation in Georgia. I had a sense it was a problem here, too. And it was.”

Unfortunately, the law did not require that the GBI had to actually test the rape kits, or even break the evidence seal.

While the previous GBI Director advocated annually for additional scientists since SB 304 became law, Reynolds presented the first budget request that cuts scientists to their crime labs. One of those labs is located in Pooler.

On the continuing and mounting backlog, Holcomb asserts, “I remain committed to pursuing justice for survivors. We need to ensure we have systems in place to test evidence in a timely manner so that perpetrators can be identified and prosecuted. It’s a matter of public safety, and it’s also a matter of justice.”

So how many rape kits have not been tested since the new law went into effect? It is not known for certain, since the GBI says they do not track those numbers.

But with the numbers that they do aggregate, it can reasonably be estimated that over 11,000 rape kits have gone untested over the past three years.

A crime reduction strategy made infamous on HBO’s iconic crime drama, The Wire, is the practice of “juking the stats.” On the show, Roland Pryzbylewski explains it, in part, as, “making rapes disappear.” One wonders if a similar syndrome isn’t in effect in Georgia, as in the show’s setting of Baltimore.

Apparently, Georgia knows how to collect rape kit evidence, how to transport rape kit evidence, but not how to test rape kit evidence, which is really the most important part.

Thus rapists that would otherwise be apprehended remain on the streets of Georgia.

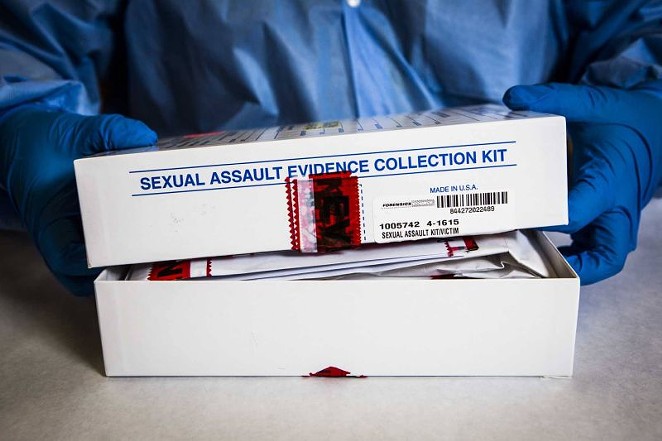

What is a rape kit?

Often called a Sexual Assault Kit, or SAK, by law enforcement, it is a collection of DNA evidence, including blood, semen, saliva, tissue, fingernail scrapings, hair combings, clothing fibers, and other evidence taken from the victim’s body after a rape has occurred.

The victim, usually a woman, can be in the emergency room for up to 10 hours after she has been raped. In Chatham County, the evidence is usually collected by a SANE (Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner). A police officer will also take a report at the hospital.

Another Georgia law, sponsored by Holcomb, passed in 2019, requires that after a rape kit is released by the GBI, it returns to the local jurisdiction to be stored from 30 to 50 years depending on the circumstances of the case.

Again, this law does not require the GBI to actually process the rape kits before transferring them back to their original jurisdiction for storage.

The GBI, in consultation with law enforcement, has the discretion to determine which rape kits will be tested and which ones will not. The ones that are tested wait an average of 312 days at one of the GBI crimes labs to complete testing.

Reynolds also testified that the GBI is looking to outsource testing of rape kits to for-profit labs outside of Georgia. Many believe this method is flawed for several reasons.

First, it eliminates science positions in the state of Georgia.

Second, you lose quality control when sending to an outside lab.

Third, you risk chain-of-custody and it must be proven in court that the rape kit was not tampered with while being transported in and out of state.

Finally, when a rape case does come in front of a jury, the scientist who tests the kit has to appear in court to testify, leaving the burden on the individual counties to absorb the cost of flying scientists in from Utah and Virginia.

The Ohio Model

As a comparison, let’s take a look at how Ohio processes their rape kits, a protocol commonly considered the national best practice in testing.

When Ohio found that they had a problem with backlogged rape kits sitting on hospitals shelves and in police departments, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine, then Attorney General, faced the problem head on; starting a new unit, adding forensic scientists and insisting on state of the art lab equipment.

“It takes money and commitment,” Governor DeWine tells Connect. “Further, it is not enough just to do the testing, there has to be an ability and will to then get the case worked up for trial.”

“In Ohio’s case, half of the old rape kits came out of the city of Cleveland,” explains DeWine. “We had a dedicated county prosecutor there, Tim McGinty. Further, I gave him some money and investigators to help get the cases prepared, and worked up for trial. It worked well.”

Gov. DeWine continues, “To repeat though, you can do the rape kits, get a hit, figure out who the rapist was, but then you are only half way home. You gotta get the guy, work up the case, find your victim, and prosecute. Usually very doable, but you gotta do it!”

Some other facts about Ohio: their crime lab tests rape kits in about 3 weeks, from receiving to completion, vs. Georgia’s 312 days, or 44.5 weeks.

Ohio tests every kit that is submitted. Additionally they test the entire kit, including underwear, other clothing items, and any other evidence from the crime scene.

In comparison, Georgia doesn’t test all rape kits, nor does the GBI test the entire rape kit, they only select certain swab(s) to test. The GBI also asks police departments not to include anything in the rape kit other than the swabs taken from the victim’s body, therefore clothing and other fiber evidence generally goes untested in Georgia.

In Georgia, when a rape kit is a returned to the jurisdiction in which it originated, if the police or District Attorney’s office want more samples tested to prove their case, the rape kit goes in the back of the line at the GBI to wait another 312 days for the requested tests.

There is a process in which law enforcement can request priority testing, whereby the rape kit can cut in line ahead of the other ones waiting to be tested.

Needless to say, testing the entire rape kit the first time like Ohio does seems to be a more efficient method.

When Ohio tested their backlogged rape kits, they received nearly 40% CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) hits. In Georgia, when testing the rape kits that were submitted to the GBI as a result of SB 304, the GBI only received approximately 15% CODIS hits. The biggest difference between the two systems is that Ohio tested every piece of evidence that is submitted and Georgia does not.

In short, CODIS is the FBI’s DNA database. When the results of a rape kit are entered into CODIS, it can help solve rape cases where there is no suspect; furthermore, if there is a known suspect in the rape case, the DNA entered into CODIS can help to solve other cases, like serial rape, homicide, burglary, and gang activity.

However, CODIS is only as good as the DNA that each state enters. So when one state fails to do their part, the entire system suffers.

Ohio Gov. DeWine says, “Because people move around, including criminals, it is important that all states do the rape kit testing.”

“Getting rapists locked up is what the criminologists call a specific deterrent. That person will not be able to commit crimes for as long as they are locked up,” says DeWine. “Removing them (rapists) from society will reduce crime during the period they are locked up.”

The cost of testing

According to the National Center for Victims of Crime, the cost of testing one rape kit ranges anywhere from $400 to $1,000. Since the DNA contained in a rape kit can help solve other crimes and cold cases, many believe testing rape kits to be a good value when it comes to fighting crime.

Additionally, rapists are commonly recidivists and not specialists, meaning statistically they commit a myriad of criminal offenses, including robbery, burglary, and homicide. When the CODIS is used appropriately, rapists are more easily and more specifically identified.

In response to the value of a rape kit, Ohio Gov. DeWine states, “Needless to say, it is cheaper to lock them (rapists) up.”

Statistical trends across the United States have proven that when a rape kit is not tested, disproportionately the victim is a woman of color.

In January 2017, the GBI started the year with 10,314 rape kits; 3,164 of those were a result of SB 304. The other 7,150 were the “normal” backlog at the GBI crime labs. The GBI reports that 9,810 rape kits have been submitted in the past three years, and in that same period of time, 8,538 rape kits have been tested (out of the 20,124 total).

Since GBI Director Reynolds reported last month that there were 768 rape kits waiting to be tested, that leaves about 10,818 unaccounted for, most likely returned to the original jurisdiction untested and deteriorating for up to 50 years before they can be destroyed.

Why does it matter? Each rape kit is the account of a horrible experience, it contains DNA evidence along with the tears of the victim — these kits deserve respect.

Rape is the most under-reported crime, and while some think that “women lie,” the incidents of false reporting of a rape are no more than false reporting of other crimes. Testing rape kits also exonerates suspects when needed.

How can Georgia do better?

Priority one, increase the budget to add more scientists and lab equipment, so that every rape kit can be tested every time — the entire rape kit.

While both Gov. Kemp and GBI Director Reynolds inherited this problem in 2019, it is negligent to propose budget cuts when a less than adequate job is being done. The GBI has trained scientists that can test the rape kits. They just need more of them and additional equipment. Not testing rape kits is reckless and a public safety hazard for all Georgians.

Both Gov. Kemp and Director Vic Reynolds declined comment for this article.

Other rape bills at the Georgia Capitol that are waiting for a committee hearing:

• HB 629, sponsored by Representative Scott Holcomb, would if passed provide for the refusal, suspension, or revocation of the license of a physician who has committed a sexual assault on a patient.

• SB 287, sponsored by Senator Harold Jones II, would if passed remove the statute of limitations on the offenses of rape, aggravated sodomy, and aggravated sexual battery.

Senator Jones says, “We knew that we needed to increase the statute of limitations on rape from 15 years; but then the question became to what - 20 years, 25 years? To some extent, they were arbitrary numbers. The better route is to have no statute of limitations. It (rape) has such a life-changing impact, why would you put a statute of limitations on that?”

If you want to know about the backlog of rape kits, the HBO documentary, I Am Evidence is powerful. Also, the documentary The Hunting Ground investigates the prevalence of rape on college campuses.

Statistically rape affects more women than men. Statistically more men make laws and establish procedures.

Each rape kit contains a horrible experience. “Test the damn kits.”