NOT FEELING St. Patrick’s Day? I’m here for you.

Close your eyes, and imagine all the River Street revelers up to their necks in litter-strewn salt water.

Curmudgeonly fantasy? Maybe not.

Yes, it’s time for another healthy dose of sea level rise realism. I may commit to doing this every six months or so.

My last foray into this subject was due to Hurricane Irma. This one is due to a different visitation, that of Professor Richard Dagenhart’s urban design studio from Georgia Tech.

Last Saturday they presented initial findings from their semester-long project to interested parties at the Parkside Worship Center on Washington Ave.

First, let’s learn a little terminology, as it will help in visualizing the future they are looking at.

Mean Higher High Water (MHHW): This is our baseline, our zero, to which we will be adding increments of increased sea level. It is not an average of all tides, high and low. It is the average of all regular high tides, excluding periodic anomalies like a King Tide.

Unusual High Tide Events: Events such as the previously mentioned King Tide, a “Super Moon” Tide, etc. Locally, these events tend to be the MHHW plus 12 to 18 inches. These not uncommon events sometimes inundate Highway 80 out to Tybee Island. Keep that in mind — that is just MHHW + 18 inches.

Storm Surge: This is the temporary rise in sea level caused by low air pressure, strong prevailing winds, and combined wave energy from a large storm system such as a hurricane. Individual large waves then ride on top of this increment.

Hurricane Irma had a storm surge of 4.7 feet at Tybee Island, and coincided with a King Tide. And remember, despite just days earlier being the strongest Cat 5 hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic, Irma’s eye passed well west of Savannah as “just” a Tropical Storm. It could have been much, much worse.

Seal Level Rise (SLR) will be added to all of this. It actually moves the baseline itself, the Mean Higher High Water (MHHW). This could be anywhere from 1 foot to 6 feet (or more, given time).

To get a good look at what one foot of sea level rise over the past century looks like, take a quick drive up to Hunting Island, S.C. and walk the beach, noticing all the “ghost trees.”

This gradual rise that we have already experienced is mostly associated with a 2-degree rise in ocean temperatures, and the resulting expansion of those waters. Ice melt is not the primary cause.

So when can we expect to experience future rise in sea level?

Professor Dagenhart exhorts us not to get caught up in the “when,” but instead concern ourselves with the “how much.”

“We have to begin thinking about sea level rise in feet, not time. Time is elastic. We know seas will rise, because they already have, and there is scientific consensus that the rise will continue. Instead of arguing when we must act to adapt, we need to focus on what we should be doing and planning now, for IF seas rise 1 or 2 or 4 or 8 or 12 feet in the future. We can plot any rise of sea level on the ground, now, and know the consequences. If we try to plot time, we would be on a fool’s errand.”

Think of it this way – if you live in an area where home theft and invasion are a threat, are you going to obsess over exactly when it might occur?

Or are you going to go out and buy the dog, the deadbolts, the alarm system and the cameras in order to prepare for the threat, whenever it may come?

The latter is the smart route, versus crossing your fingers and hoping that it just won’t happen (also a popular route).

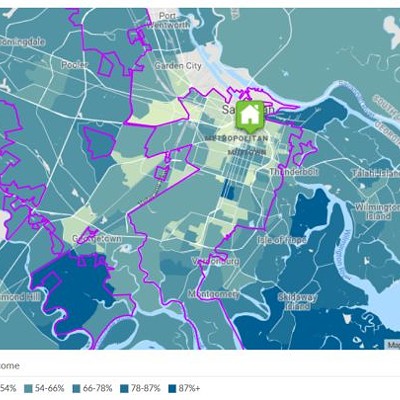

Here are some numbers for two scenarios that the students looked at for metro Savannah. First, MHHW + 3 feet of sea level rise, with unusual high tide events on top of that – 13,512 houses and 24,322 people would be affected.

Second scenario, add to the previous example a storm surge of 4 feet (less than experienced with Irma). Now 49,135 houses and 95,863 people are affected. Wow.

So what can we do? Students outlined two basic responses, with too many sub-headings to recount:

1. Retreat to High Ground. Perhaps the most obvious response, but easier said than done. How is this accomplished?

Renters can just move. Homeowners can sell, but how long will there be buyers for these at-risk houses? And at what prices? Another strategy would be to hold on and hope for some sort of government buy-out sometime in the future, when and if retreat must be mandated.

As to where this higher ground is: Tybee, as I’ve said before, is pretty much screwed. It’s just a matter of time.

Whitemarsh, Wilmington, and other islands have interior areas high enough to remain safe. However, the fringes of these islands will be flooded, splitting them into more, smaller islands, and probably isolating them from the mainland as roadways become unusable.

The area east of the Truman Parkway will at some point become a new island, with Skidaway Road running along its crest. With redevelopment (more on this later), the area may be able to accommodate many of those leaving the “old” islands, if they don’t just choose to move further inland to Pooler, Macon, or Atlanta. It is likely that this new island can remain well-connected to the mainland.

2. Live with/on the Water. You know some people are going to be obstinate to the last, or just not have the resources to move. So, there are strategies for living with increasingly chronic flooding, but eventually a lot of homes are going to be lost unless they can be periodically moved (don’t knock those wheels off your mobile home), elevated high enough on stilts, or even become free of any foundation and float with the rising waters.

There are actually some very interesting examples of floating communities both in America (ex: Sausalito, CA) and abroad (ex: The Netherlands, of course). Some of these are clusters of boathouses, while others are actual floating buildings with floating “streets” connecting them, all tethered to the shore.

But the land that will be directly impacted by sea level rise is just one aspect of these students’ studies in Savannah.

Here are four other related issues:

Stormwater Management. Sigh. In addition to sea level rise and storm surge, we have to also deal with that water falling on the land as precipitation.

Already, we are not doing a great job at this, and as MHHW rises, it will become more difficult to drain the land.

Problems include: large expanses of impervious surfaces (roads, parking lots, structures) that don’t absorb water, creating extra runoff; a very low slope to the land in most areas, making it difficult to move the runoff; and lots of structures built in flood zones (which will expand), where the runoff wants to go.

For at-risk structures, tactical solutions include flood-proofing buildings that are worth the cost, and evacuating those that are not.

Strategically, students are examining ways to enhance the Casey Canal parallel to much of the Truman Parkway, adding to it several small and/or one large reservoir that would allow stormwater to recharge back into the ground aquifer.

This would help in combating saltwater intrusion, rather than just draining out to the Savannah River and then the Atlantic Ocean.

The Truman Parkway. This subject is going to cause the most coronaries. The students are looking at several options for major changes to a piece of hugely significant infrastructure that was just completed a few short years ago.

But as Dagenhart says, “It never should have been built like that.”

There’s not room to go into all three preliminary options presented, but the one I found most compelling was to re-integrate portions of the Truman into the “ground-level” street grid, mainly in more northern sections (DeLesseps and above).

While this would require new intersections that would slow north-south drive times, it would greatly help to reconnect neighborhoods east to west, and mitigate traffic pile-ups like we see daily at Victory. It would also free up land that could be used as public greenspace and enhance drainage into the Casey Canal.

Retrofitting Victory Square, et al. While on the subject of Truman and Victory, the students also looked at how the many big-box shopping centers in that vicinity might be redeveloped.

Basically, they are exploring a phased approach to cutting smaller streets and blocks back into these areas, while “re-greening” low-lying portions that are adjacent to the Truman Parkway and Casey Canal.

If denser development were allowed here, it would be an obvious area that people could move to as they abandon areas farther east that will be inundated or chronically flooded in the future.

Skidaway Road could become a dense, mixed-use urban corridor with a population that could support much greater public transit investments.

Victory Drive. Finally, assuming that some of the above suggestions are implemented, it could allow Victory Drive to return itself to a more idyllic past, handling traffic that is primarily local rather than regional.

With alternative east-west connections opened up by integrating the Truman, and less people inhabiting the areas east of Skidaway, perhaps Victory could even be taken down to two lanes, and all its wonderful trees given more room.

I have barely been able to scratch the surface of what these Georgia Tech students presented. They covered an entire wall in two layers of diagrams, illustrations, and bullet-points.

My goal has merely been to whet your appetite, as they will be presenting again at least two more times — once again to the Savannah stakeholders, with more detailed recommendations from all study areas, and again at CNU 26 in May.

You can also refer to the “Smart Growth Savannah” page on Facebook for video of this presentation and future updates.

Nick Palumbo, who has acted as a local liaison for this project, says “It’s imperative we look at how building, development, and urban design impact water. It’s all about the water, and how we’re going to live with it in the future. The sooner we plan for it — the better.”