BY THE time you read this, the votes will have been cast for who will lead Savannah for the next four years. Some will raise a toast to the results, others will drink themselves into a stupor—especially if there’s a run-off or two and we get to suffer all over again in a few weeks.

But no matter what, come that Wednesday morning hangover, we’re all gonna wake up living in the exact same place. So everybody knock back a Vitamin C packet and a couple of aspirin, ‘cause there’s chiton of work to be done.

Many promises were made this election season about helping our youth, specifically the ones dropping out of school, stealing cars, running drugs and shooting up the streets and each other. Now we’re going to see who was just blustering and who has actual solutions—whatever those are, they’d best come durn quick and not include building more prisons.

If the new council configuration is at a loss about where to start, they ought to ask Semaj Clark, since he knows what actually works. The 18 year-old grew up in the housing projects in Watts, Calif., bouncing in and out of foster homes and juvenile jail, blindly following the tragic trajectory of so many young men of color.

When he was 15, his parole officer sent him to the Brotherhood Crusade, where a couple of community mentors slowly opened his mind to the possibility of a new direction—not by preaching at him, or funding a community center he’d never attend, but by showing up and taking him out to dinner.

One drove him to and from school every day so he could avoid the unsavory characters that harassed him when he walked. Another gave him some walking around money so he wouldn’t have to deal drugs for cash.

When he faltered, they welcomed him back unconditionally, time after time after time.

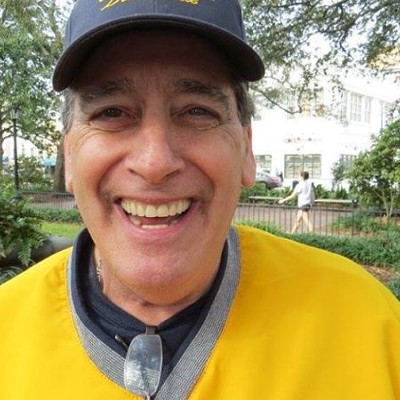

“I was like a yo-yo,” admits Semaj, flashing what may be one of the most charming smiles ever created. “It took a year for me to believe they were really there to help me. When you come from a broken home, you have trust issues, you know?”

Slowly, his grades improved, became notable even, and he started college. His heart softened, and he reestablished his relationship with his mother. His path lit up with possibilities as he stepped into the role of advocate and ambassador, sharing how genuine attention and true patience make all the difference when trying to turn others’ lives towards the positive.

In May, Semaj was featured in the Los Angeles Times for his standout efforts. In August, he met President Obama.

In October, he and five Crusade brothers were invited to Savannah to tell their stories at a Community Safety Forum hosted by the Chatham County Juvenile Court.

Local judges, law enforcement, school board members and elected officials were blown away by Semaj’s earnest charisma and concrete plans for change.

Later that evening, while chilling on River Street, Semaj and a brother met some local kids—exactly the types they hope to reach with their message—and followed them back to Yamacraw Village.

The kids brought out a gun and tried to rob them, so he and his friend ran. Semaj took two bullets to the arm and one to the back.

He’s now paralyzed from the waist down. The prognosis is that he’ll never walk again.

From the two-dimensional world of internet news, it’s a story of heart-wrenching ironies: The non-violent youth advocate shot by criminal youth.

Worse yet, the 17 year-old charged with the shooting was supposed to have been at the public safety forum that morning, where he might have imagined bigger, better options for his night that didn’t include going to jail for aggravated assault.

But the most astounding twist is that after experiencing the worst of Savannah hospitality, Semaj wants to stay here.

“I feel like I can really make a difference,” he told me last week when I brought him some early Halloween candy. (He’d been missing the spicy chili kind he gets in L.A., so I hunted some down at the Super International on Waters Ave.)

When I asked for his room at the hospital, I learned he’d been advised to use an alias in case of retribution from the shooter’s friends. Was he scared?

“Nah, I’m from Watts, remember?” he laughed, setting aside his journal to peer into the bag. “But I’m cooperating.”

Then he said quietly, still beaming, “I know it’s hard to believe, but I’m happy. I’m not someone who can be brought down. To me this is a sign. It may be rough these next few months, but I have faith that everything happens for a reason. I want to help, and this is where God has put me.”

His mom, Cynthia, sat by his side as we talked about his plans to establish a local non-profit based on the program that mentored him. He’s also been in contact with administrators at Savannah State, where he’d like to transfer to major in Political Science and Economics.

His eyes gleamed as he explained the concept of restorative justice—bringing together victims and offenders as part of the same community—and how that simply referring to those who have served time in prison as “returning citizens” instead of ex-felons can help prevent recidivism.

Semaj also spoke of the importance of forgiveness, and says he’s not angry at the boy who pulled the trigger on him.

“I was given a lot of chances,” he said, scratching at the scab on his arm where one of the bullets grazed him.

“I hope I get to talk with the kid who shot me, because I want him to know that there is hope for his life.”

How’s that for grace? But he and his mentors know change takes more than one conversation.

Correcting behavior with compassion is an effective solution but a Sisyphean task, says Dr. Renford Reese, who accompanied Semaj to Savannah and runs the Reintegration Academy at Cal Poly Pomona for formerly incarcerated young men.

“These young men are living in a culture of dysfunction,” lamented Dr. Reese after the shooting. “People try to paint a rosy picture of black male transformation, but there’s nothing easy about it.”

And here is Semaj, compression pumps around his legs, already doing the work. In between nurse check-ups and visits from community leaders, he’s on the phone, counseling local kids who are looking to turn their lives to the sun but don’t know where to start.

He’s also already more educated about Savannah politics than most of us citizens, says Pastor Thurmond Tillman of First African Baptist Church.

“When I walked in, he was watching the city council meeting on TV,” marveled Pastor Tillman. “I came back the next day, and he was watching the school board meeting!”

Such enthusiasm for civic duty ought to stop all of us in our election-saturated tracks. Not that our cynicism is unwarranted: How many people have fled Savannah this year, having given up on its subpar schools and pitiful job market and dire crime situation? How many more would if they could? How many didn’t even bother to vote?

Yet here is a bright soul not only resisting despair, but banishing it. I can’t think of anything more humbling or inspiring.

Semaj left last week for the expert rehabilitative care of Atlanta’s Shepherd Spine Center, but he promises he’ll be back as soon as the doctors approve. In the meantime, his medical bills mount, and there will be many more expenses as he learns to navigate the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

Sports fans may be reminded of Devon Gales, the Southern University football player paralyzed last month while returning a kickoff against the University of Georgia. The town of Athens and the rest of Dawg Nation have rallied around Gales, footing the bill for his family’s travels and raising money for his recovery.

Doesn’t Savannah owe the same to Semaj?

There is a GoFundMe site, searchable on Facebook by #SupportSemaj—I hope every Savannahian will give a little bit.

Consider it an investment. If Semaj Clark accomplishes even one percent of what he says he wants to do for Savannah, the returns will come back a millionfold.