IN THE mid-1950s, Savannah had a changing of the guards.

Back then, downtown was a sad grid of broken windows and empty storefronts, and city leaders couldn’t wait to erase it all to build glassy, sharp-cornered banks and chunky parking garages.

That plan met a snag when society columnist (hey, now) Anna Colquitt Hunter gathered up some girlfriends to fight the powers-that-be. Even though those in charge touted their planned decimation of downtown as “progress,” it was really just the same old stupid shortsightedness, and Hunter knew it.

She and her cadre of rebellious Southern belles were the innovative ones, envisioning a future Savannah that valued—and profited from—its heritage and history. Can you imagine how radical and downright crazy those ladies must have seemed, storming City Hall and shaking their pocketbooks at the greedy carpetbagger developers?

Yet they managed to win over the old guard, and the Historic Savannah Foundation went on to save over a thousand buildings from the bulldozers and literally change the city’s trajectory. Their high-profile petitioning also ushered in an era of civic involvement and social change that included important communal infrastructure (hello, sewage system) and robust, integrated participation in the Civil Rights Movement.

I was thinking about those forward-thinking women last week as I attended a couple of events that portend that Savannah may once again be at a similar kind of juncture, where outdated notions could give way to a brand new zeitgeist.

On Monday, writer and activist Kristopher Monroe delivered a lecture to the Telfair Academy Guild called “What’s Art Got to Do With It?” He focused on successful community revitalization projects in other cities that incorporated public art, from Philadelphia’s anti-graffiti murals to Houston’s Project Row Houses, which began as art squats and evolved into a vibrant, mixed-income neighborhood that offers free childcare to single moms.

The TAG audience seemed a tad skeptical. It would be gauche to call this elegant, educated group “old school,” but the guild is built upon well-established ideas about art and architecture that do not include Section 8 housing and painting historic buildings. (At least one attendee was still testy about SeeSAW’s “Before I Die” chalkboard that went unappreciated by some neighbors.)

But Kris—a Deep fellow and a member of Step Up Savannah’s Neighborhood Leadership Academy—hopes to freshen their attitudes as the newest member of the MPC’s Site and Monument Commission. He’s also the board chair of ArtRise, which makes its home in the Starland District, which is arguably—or not—the city’s most successful arts-integrated neighborhood:

Housing is still affordable as is workspace, thanks to the new Sulphur Studios. Starland’s commercial spots thrive with quirky new stores like Gypsy Girl Vintage and NOLA Jane, and Cha-Del’s provides just the right mix of friendly sketchery.

But how to make it last? Usually, the second a neighborhood gets a little shine, real estate jacks up and displaces the starving artists and low-income citizens who made it a cool urban utopia in the first place.

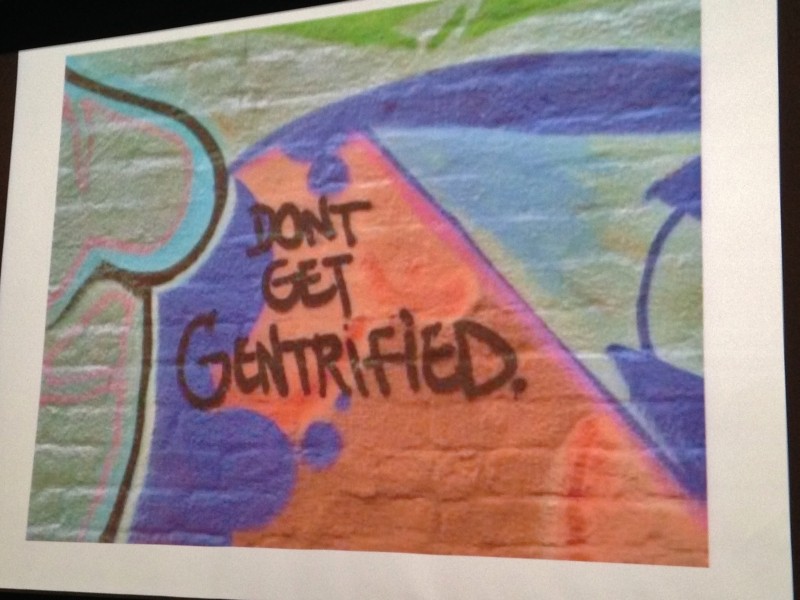

“The biggest challenge is gentrification,” said Monroe of any revitalization effort. “You have to involve all the stakeholders.”

Oh, the G-word. Savannah has seen its share: After HSF made it attractive to live downtown again, entrepreneurs restored crumbling townhomes to their former finery and flipped them until only the rich could afford to buy north of Gaston.

Of course, those beautiful homes are a big part of what now drives visitors to Savannah, and HSF’s Daniel Carey confirmed that architecture is “the canvas” that connects art and preservation.

But the new guard believes that canvas belongs to everyone, not just the wealthy, and the conversation continues.

The same egalitarian approach was on the agenda later that same day at another gathering hosted by the newly-minted Port City Cultural Collective. (At first, I sniffed hard at the use of “Port City” for Savannah, since the city receives not a penny of direct revenue from the state-run Georgia Ports Authority. I chilled out when it was explained that it’s a nod to the C-Port reference made famous by late local rapper Camoflauge, but to these SHEP-sensitive ears, that sobriquet does no justice towards local economic development. Just sayin’.)

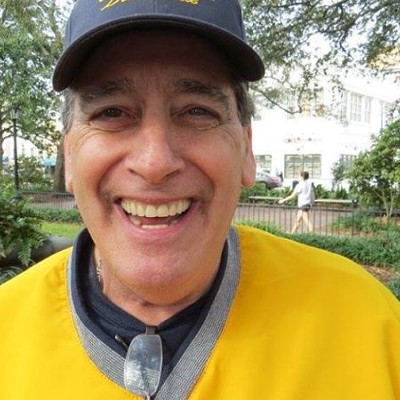

A.J. Perez and the rest of the PCCC folks have their heads and hearts in exactly the right place, inviting city attorney Brooks Stillwell down from the Gold Dome to a more populist platform to talk about the city’s future. (I think we can all agree that Savannah’s conscious citizenry needs more space—the walls of the Sentient Bean were full to busting.)

Interviewed live by ArtRise’s Clinton Edminster, Stillwell presented a bird’s eye view of the city’s $400 million roster of current development projects via a full-color map, the squares spread out like a checkered fan. He painted a rosy picture of minimal debts and a bustling tourism industry that someone described in a murmur as “sugar-coated.”

Now it was time for the PCCC audience to be skeptical, the unspoken realities of minimum-wage service jobs and crime hanging in the air. The idea that tourism is Savannah’s only economic savior is an idea that’s moved solidly into the “old school” category, and the new guard ain’t buying it.

One of the points at stake is the acknowledgement of the burgeoning arts economy operating independently of SCAD. Another is that Savannah’s commercial successes cannot be celebrated without taking into account its social problems.

Soccer coach Dave Hutchison declared to the room that until our disenfranchised youth are “brought into the fold,” any conversation about the city’s prosperity remains incomplete. Student Eric Brown agreed, politely pointing out to Stillwell that his language regarding how crime is localized in certain neighborhoods “makes us separate.”

Yet the newbies must remember that the older minds of this village began as young upstarts. Ms. Hunter and her rabblerousers were not always so revered, and Stillwell himself was once a revolutionary young turk: In 1974, he became the city’s youngest alderman at the age of 24—you can thank him for spiffing up the once-dilapidated squares and finishing the Truman Parkway.

Stillwell enjoined that in order for Savannah to move forward, people have to step foward to make it happen.

Do you live here? That’s you. (Live elsewhere and enjoying your visit? Buy local.)

Have a problem with a developer’s vision for Broughton Street? Go shake your pocketbook at the streetscape planning meetings.

Pissed at the cops? The Citizens Police Academy starts its next 14-week course on Feb. 12.

Batshit crazy and ready to rumble? Run for City Council—rumor has it there may be several district seats up for grabs in November.

The time has come for the old guard to pass the baton, and as the new guard gears up for its inaugural sprint, it behooves us take with it the lessons of those who have come before.

We’re the stakeholders, and I sure hope we’re prepared for a long run.