LIKE SO many of my columns, this one starts with being lost.

I thought I knew where I was going as I cruised with my 11 year-old daughter to hear our homegirl Starcastle play at the World’s Smallest Music Festival (in a private home, of course, because that’s the only way people of all ages can see live music in this town, don’tcha know.)

Then the Post-It note on which I’d written down the address suddenly evaporated, and I found myself driving around an unfamiliar neighborhood on the Westside. At first, it didn’t look too different from our street, folks sitting on their porches and fanning themselves in the muggy, buggy twilight. Some nodded, some waved.

On the next block, the houses got shabbier, the people less friendly. I drove a bit more, trying to remember the house number. I realized I’d have to consult my phone and pulled up outside a cinderblock cottage with several cars parked on the lawn.

Three men drinking from paper bags glared at us from the cement steps.

“Um, mom, I don’t think this is the place,” murmured my daughter.

“Well, it could be,” I said briskly. The largest of the men jumped up and started walking towards the car. “But it probably isn’t.” I locked the doors.

It felt terrible to assume he was a threat. I’ve tried to raise my kids to be comfortable anywhere, around all kinds of people, and here I was, rolling up the windows like Chevy Chase in Vacation.

I also knew a man had been shot and killed very close to here a few days before and saw no reason to idle.

We sped off to find a well-lit gas station to message for directions.

As I texted, my daughter plucked the Post-It from between the seats, revealing that the gathering was on a 600 block on the east side, not the west. It took less than ten minutes to get across town, and in that time I delivered an awkward lecture, worried that my hasty exit had given her the message that the neighborhood we’d just left was inherently dangerous and that the people who lived there were “bad.”

“No, Mom, nobody thinks that,” she said, patting my hand. I kissed her head and told her how I wished that were true.

We talked about how violent crime is a huge concern for everyone in Savannah, but that the conversation about it is often reduced to “us” and “them,” as if there were a dividing line between criminals and the rest of us.

“Well, the criminals have to grow up somewhere,” she replied, sounding wiser than 11.

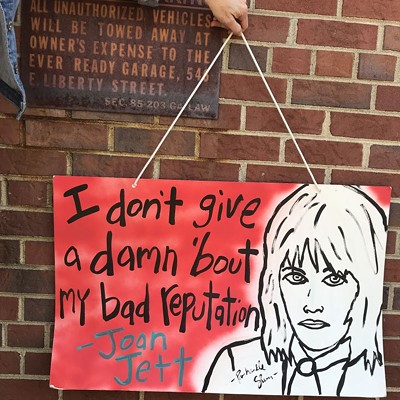

We enjoyed the music that night, but ever since I’ve pondered and re-pondered my own fears and beliefs about Savannah’s “bad” neighborhoods. The blocks where bullet shells shower the streets as often as rain, the housing projects where people bleed from gunshot wounds almost every day now, the places plagued by drugs and violence and witnesses are too traumatized and terrified to come forward.

As a denizen of a midtown neighborhood that sees its share of crime but ostensibly falls in the category of “good”—as in no one gets shot at on a regular basis—I struggle with how to support those who live in these troubled communities without coming off as an interloper, or, if we’re being honest, a condescending asshole.

Engaging those who have given up on the police and city leadership is hard. It requires stepping beyond our own beaten paths and cultural comfort zones, even if we think we’re pretty cool because we can quote Straight Outta Compton in its entirety (the album, not the film, children.)

My own awkward attempts haunted me as me and my kiddo were rollin’ in our Benz-o (yes, the Absurdivan has been replaced—with a Mercedes older than most of my coworkers.) Fortunately, there are people showing a better way.

The committed folks of Solidarity in Savannah show up to the site of every shooting within the city limits, letting the surrounding community know with signs and chants that they are not alone. Some days, residents look warily at the protestors, keeping their distance. Other times they come closer, and genuine conversations emerge.

Every. Single. Shooting. SIS has been busy. With only two days without an incidentof gun violence since August 7, the group has responded to each scene within hours, organizing a small demonstration the next evening, or in some cases, the same day. The intent is to change the social norms surrounding violent crime in challenged neighborhoods—that it’s acceptable, unsolvable and endemic.

“We’re following the public health model that treats violence like a disease,” explains SIS founder Ylana Abbot of the immediate procedures.

That approach, known as Cure Violence, disrupts the cycle of violence with a specific protocol: First, trained and trusted “interrupters” help victims and families process grief without retaliation, inhibiting the spread of the violence. Then they identify and “treat” the highest risk individuals with counseling and outreach.

Finally, the larger community is encouraged to show up—an inoculation against further infection.

The program reduced shootings in Chicago by 67 percent in 2000 and has been implemented in dozens of cities worldwide. It’s already had enough of an impact that the DA’s office recently tapped SIS to oversee the community engagement piece of Operation Ceasefire.

Vowing to step higher and further from my privileged bubble, I found the group at the Fred Wessels Homes on East Oglethorpe the day after 20 year-old Marquail Banner was killed—the 25th homicide by gun this year.

“Forty bullets on the ground. Do you hear me? Forty!” hollered “hype man” Shawntray Grant of the Bullhorn Crew, amplified by his weapon of choice. “You got kids who play all over this park!”

Part of each SIS action is to connect with the children of the neighborhood. Loop It Up Savannah and Emergent Savannah provide art projects and fun for the kids who may have seen flashing police lights and possibly blood the day before. Each watercolor painting and chalk mark is a tiny step towards a calmer, creative world, and free popsicles also cultivate smiles.

The easy picnic atmosphere also helps the adults know that they’re supported and protected by a bigger community, so maybe, eventually, they’ll feel safer breaking the code of silence that prevents proper police investigation and keeps neighborhoods strangled in the patterns of criminal activity.

Perhaps it’s already working: WTOC reported last week that anonymous tips to Crimestoppers are on the rise and have led to several arrests.

But fear and complex loyalties still rule.

“You can’t give up, you gotta be patient,” counseled grandma Elaine Mercer as she colored with markers.

“This is going to take time.”

The next evening, I went back to the west side, where SIS joined with Savannah Lives Matter and the Savannah Youth City for a rally with the families of previous fatal shootings. I brought my daughter along, hugging her tight as we stood in the light rain listening to the list of dead sons, cousins, fathers, nephews, uncles.

Tears fell as a rainbow appeared in the eastern sky. Ylanda checked her phone.

“I’ve got to go,” she said, grabbing her keys. “We just got word that a 2 year-old has just been shot over at Clearview Homes.”

My daughter cried on the way home—a five minute drive—for another child harmed. I trembled with the truth of what the residents of Gordonston and other members of the Eastside Alliance with bullet holes in their windows already know: That the borders between “good” and “bad” in this little city are illusions.

Change can only come when we realize that all of us live in the places in between.