SAVANNAH HAS been growing and expanding throughout its long history. The area being considered for the future Canal District officially became part of the city in 1854, and during the early 20th century suburban expansion pushed farther to the west.

In the past, builders were far less scrupulous about developing marginal or hazardous areas. Unburdened by flood maps and stormwater regulation, they had no qualms about building in places we would never consider doing so today.

If land near an expanding city was viable it would not go undeveloped. Yet development largely skipped over this seemingly prime location relatively close to downtown.

The reason is clear: much of the proposed “Canal District” is low-lying, unbuildable wetland.

Looking at historic Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, which document every structure no matter how insignificant, and 20th-century photos, it’s evident that there was never very much in the area.

A 1951 aerial image of the site shows that nearly 70 years ago it looked very much like it does today.

At most a handful of industrial structures occupied the site, in addition to the monumental waterworks building, which by necessity was located close to a water source.

If it wasn’t good enough for Savannahians in decades past, why should it be the City’s top choice now for a major civic amenity, in an era of sea-level rise, monster hurricanes and when devastating floods are becoming all too commonplace?

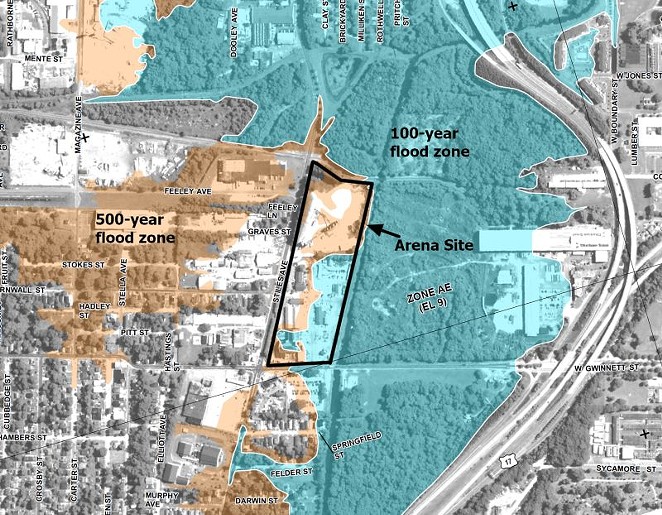

The Springfield canal at the heart of the “Canal District” marks the geographic low point between two regions of higher land, downtown and Carver Village. In talking seriously about building the arena adjacent to the canal and redeveloping the area, the City must come to grips with the fact that any development would face significant flood risks—risks increasing year by year with climate change and sea-level rise.

It must also grapple with longstanding issues of environmental contamination from the area’s past uses and the continued presence of heavy industry. Among the “areas of concern” for the arena site itself are underground fuel tanks, buried medical waste, asbestos, and coal residue. Adjacent sites are known to have benzene, lead and other contaminants.

Much of the new arena site sits within a hundred-year floodplain, including most of the area proposed for mixed-use development depicted in the renderings.

The canal is essentially at the same level as the Savannah River, with adjacent parts of the arena site rising just 7 feet above mean sea level. The remainder of the site rises to about 14 feet and is mostly within the 500-year flood zone.

Over the assumed 50-year lifespan of a municipal arena, sea level rise will ensure the flood zone boundaries will only expand. Given the uncertainty of a changing climate, it seems unwise to build such a significant city asset (let alone an entire redevelopment district) with such little margin for extreme rain events.

The proposed arena development will have to comply with the City’s extensive stormwater and water quality regulations. According to consulting engineers Thomas and Hutton, “it is not feasible to provide complete stormwater detention for flood control and sizeable water quality treatment on the proposed civic center/arena site.”

To meet the requirements, they propose widening the canal to 100 feet from its current 25 and upgrading a pumping station, which would allow the canal to manage 100-year storms.

The cost: at least $33 million.

But widening the canal also carries the risk of disturbing contaminated ground to the east and triggering “extensive environmental remediation.” As an alternative, they suggest expanding a detention basin north of the site into a major water feature consistent with earlier “Canal District” visions.

Neither of these improvements is part of the $140 million arena budget.

Hurricanes present a separate and perhaps even greater source of concern. Storm surge raises the base sea level, meaning that no amount of detention or pumping can save a low-lying site from the rising waters associated with a major hurricane.

According to NOAA SLOSH models, most of the proposed “Canal District” could flood in just a tropical storm and the arena site itself would be underwater with a category 2 or greater hurricane at high tide. SLOSH models do not account for rain and river flow, so if a storm like Irma dumps rain upstream the impacts could be even more severe.

In contrast to the existing Civic Center, the city’s current evacuation rallying point for citizens without transportation, flooding either at the new arena or on nearby roads could make it extremely risky to use the building as a storm shelter or for evacuations.

And what about the wetlands adjacent to the arena site? While the City faces relatively few regulatory obstacles building on the arena site proper, most City-owned land nearby would be considered federal jurisdictional wetlands and administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

This includes nearly all of the City-owned parcels to the northeast and much of the private land to the southeast across Gwinnett.

Any development would require permits and extensive scrutiny from both the Corps and possibly also from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division. Since these agencies frown on filling wetland, the development would need an extensive mitigation plan, including offsetting any wetland losses with improvements elsewhere. While not technically impossible to develop, it would be a drawn-out and extremely costly proposition.

Even if the wetland areas could be developed, why would the city willfully pave over one of the largest remaining swaths of green space adjacent to downtown? Cities increasingly appreciate the value of ͞green infrastructure͟ and are heavily investing in restoring wetlands. More development in the area would further stress a natural resource other cities are paying to preserve.

Even though downtown Savannah boasts celebrated landscaped parks and squares, the area lacks any natural green spaces. As the Canal District designers have recognized, the area has great potential for greenways and other recreation paths, which would be a tremendous asset to residents of both the west side and downtown. There is no guarantee, however, that in building the arena we would also receive these amenities, especially if money will be needed for parking garages, road improvements or shuttles.

Part of the Canal District vision includes using the canal as a further recreational destination for paddlers. The Springfield Canal drains nearly 7 square miles, including most of Savannah’s westside and a great many industrial uses from junkyards to metal processing.

“The canal itself is stagnant and in many parts unshaded, factors that facilitate bacterial growth and poor water quality,” according to local environmental expert Todd Holloway.

There is so little natural flow in the canal that a pumping station, located just north of Oglethorpe Avenue, is needed to push its water into the Savannah River.

Optimistic renderings aside, it’s unlikely we’ll see kayakers paddling by regardless of how much investment is poured into new surroundings.

Alternative arena sites closer to downtown face few of these environmental challenges. Downtown Savannah sits on a bluff 40 feet above the river, ensuring it remains high and dry in the worst flood.

While much of Chatham County would be underwater if a category 5 hurricane scored a direct hit on the city, the historic district would remain an island of dry land.

The downtown alternative sites also avoid costly headaches involving soil contamination and stormwater detention. Given the possibility of other sites on higher land, prudence would advise against such a low-lying site.

Next week I’ll conclude with a look at the economic implications of the arena in the Canal District.