HERE'S A FACTOID that might surprise even the most studious Savannah bookworm: When the Carnegie Library opened its thick double doors in August 1914, it didn't just have the distinction of being the city's first library to serve black citizens—it was Savannah's first freestanding public library, period.

The stately, two-toned brick building on Henry Street has long served as a beacon for African American education and accomplishment. In 1903, the City of Savannah had partnered with the Georgia Historical Society to put a small library inside Hodgson Hall on a temporary basis. While it was ostensibly “public,” segregation was still in full effect, and only Savannah’s white denizens were welcome.

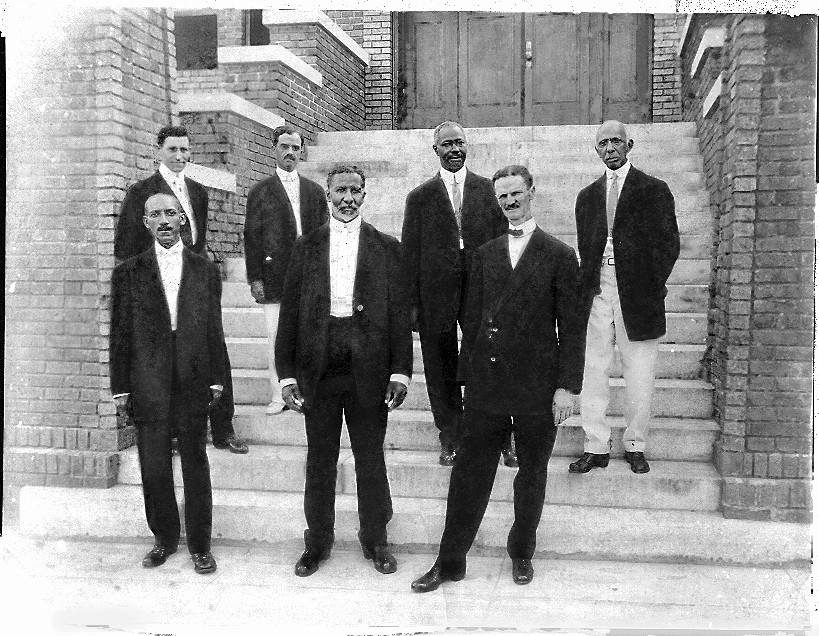

A group frustrated by the efforts to deny black people access to the city-sanctioned library formed the Colored Library Association of Savannah in 1906, and its members set out to create a clean, well-lighted place of their own.

The first Library for Colored Citizens was housed at the corner of Hartridge and Price Streets and stocked with donated books and magazines. As the collection and use of the space became established, the association petitioned self-made millionaire and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who helped fund almost 1700 public libraries in the U.S and hundreds more across the globe between 1859 and 1929. The library board received $12,000 from the Carnegie Foundation for brick-and-mortar in 1913.

“In order to get a Carnegie grant, you really had to have your act together,” explains Live Oak Public Libraries director Christian Kruse. “You had to have the matching funds, you had to have the land. You had to have a plan.”

As a matter of fact, a petition submitted in the same time period for another Savannah library was denied the first time around. The white-only Bull Street Library eventually received its Carnegie funding and opened in 1916.

“Remarkably, black Savannahians had managed to do what the white community and city leaders had not: to fund a public library out of their own pockets and raise the matching money necessary to secure the support of the Carnegie Library Association,” notes a narrative on the library’s website.

Built across from sunny Dixon Park by Savannah architect and engineer Julian deBruyn Kops, the Carnegie Library sits regally in the middle of a block of Victorian homes, its steep brick staircase flanked by sandstone orbs rising as if in triumph.

The polychromatic bricks and narrow windows are indicative of the Prairie School architecture pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright, of which the Carnegie Library is the only example in Savannah. Inside, Wright’s familiar geometric themes are everywhere, from the carved flowers on the columns to the rectangular transom that bears an etched likeness of the original founders.

“The founders were motivated, professional men who wanted their children to have something,” says Dr. Daniel Brantley, chair of the LOPL’s Board of Trustees.

“There was this idea that black people were not interested in education. That has never been true. Reading, writing, literacy—all of these were very important to the black community.”

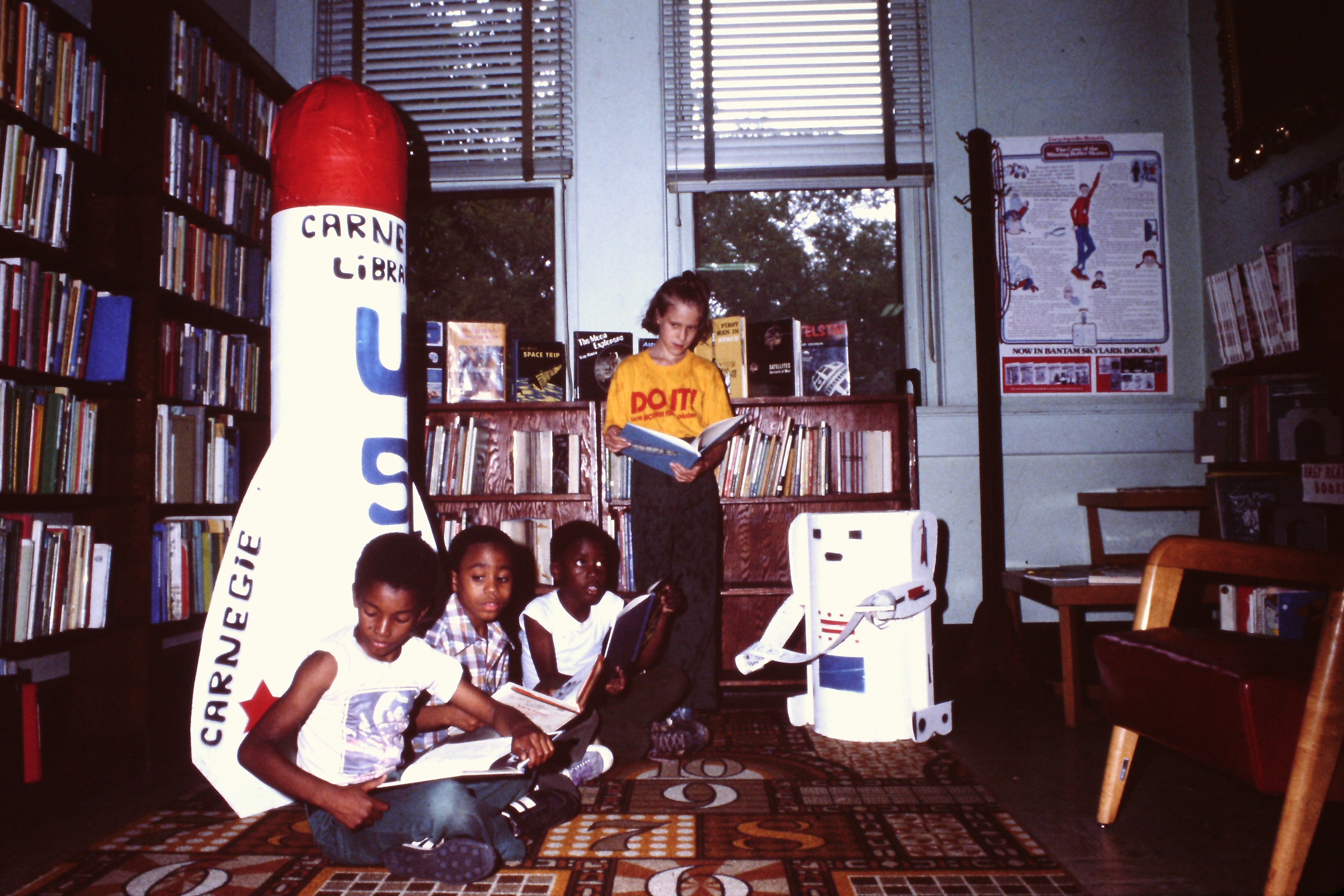

Dr. Brantley—now in his second term as LOPL chair—spent many hours at the Carnegie Library as a child, coming in through the back entrance that led what was then the downstairs children’s area (“Upstairs was only for adults,” he remembers with a definitive nod.) Inspired by his surroundings and the stories within the books he read, he went on to teach political science at Savannah State University.

“I never would have gone on to become a Ph.D and a professor if this library wasn’t here,” he avows.

Many of Savannah’s African-American professionals and leaders attribute their success to the Carnegie Library, most famously U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who reportedly “leafed through every page of every encyclopedia.”

Savannah native and Pulitzer Prize-winning short story writer James Allen McPherson, who graduated from Yale Law School and is on the faculty of the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop, has called the library a “lifesaver.”

Other notable black leaders who spent their formative years at the Carnegie include former Savannah mayors Floyd Adams and Otis Johnson, current mayor Edna Jackson and former public school superintendent Virginia Edwards. The library surely played a part in their local participation in the Civil Rights movement.

“Without the Carnegie Library, many successful blacks in this community would have had a difficult time accomplishing the many things they have achieved,” writes Edwards. “The library provided information and knowledge that was of great benefit to our overall success.”

The Centennial kicked off this week with a slew of special programming, including a historical timeline with library manager Adrienne Tillman and a group puzzle activity for kids. On Saturday, August 23, soul-stirring performer Lillian Grant-Baptiste will use stories, drums and song to engage an audience in an interactive tribute to the library’s history.

The celebration will continue into November, when a historical marker will be unveiled at the site. Library staff hopes that anyone with photos or memorabilia will consider letting their treasures be scanned for a formal display.

In 1963, the Carnegie was incorporated into the larger Savannah Public Library system after the settlement of a five-year discrimination lawsuit. While African Americans were now legally able to use any library they liked, including the massive municipal Bull Street branch, Dr. Brantley remembers it as a slow transition.

“Let’s be honest. This was the black library,” says Dr. Brantley. “It took awhile for people to feel comfortable anywhere else.”

After decades of use and sagging under the literal and perhaps metaphorical weight of so many stories, the floor of the Carnegie Library began to crumble at the end of the 20th century. A 2004 capital campaign allowed the building to be retrofitted and two wings added to accommodate an elevator, a computer area and a meeting space.

The stunning architectural integrity has been preserved both inside and out, earning the Carnegie a National Trust Award and well-deserved inclusion in Savannah’s mainstream history.

For anyone seeking to round out their experience of Savannah, the Carnegie is definitely worth a visit. The clientele is far more diverse these days, but the atmosphere still evokes the libraries of yore, when afternoons were spent peeling through onionskin pages and librarians could shush a person with simply a look. Other than the row of computers and the shelves of DVDs, there is little to disturb the notion that this is a place of quiet scholarship and welcome solitude.

Kruse points out the original shelving and wooden desk, still in the position suggested by Carnegie advisor James Bertram that allows one librarian be able to oversee the entire space.

“We’re still trying to confirm it, but I think this may be one of the last operating African-American libraries in the country,” he muses.

“This is pretty much how it looked a hundred years ago.”